Reflections for the XV Sunday

Deuteronomy 30:10-14, Colossians: 1:15-20, Luke 10:25-37

Homily starter anecdotes #1: Einstein’s little neighbor: When Einstein fled Nazi Germany, he came to America and bought a two-storied house within walking distance of Princeton University. There he entertained some of the most distinguished people of his day and discussed with them far-ranging issues from physics to human rights. But Einstein had another frequent visitor. She was not, in the world's eyes, an important person like his other guests. Emmy, a ten-year old neighbor, had heard that a very kind man who knew all about mathematics had moved into her neighborhood. Since she was having trouble with her fourth-grade mathematics, she decided to visit the man down the block to see if he would help with her problems. Einstein was very willing and explained everything to her so that she could understand it. He also told her she was welcome to come anytime she needed help. A few weeks later, one of the neighbors told Emmy's mother that Emmy was seen entering the house of the world-famous physicist. Horrified, she told her daughter that Einstein was a very important man, whose time was very valuable, and shouldn't be bothered with the problems of a little schoolgirl. She then rushed over to Einstein's house, and when Einstein answered the door, she started trying to blurt out an apology for her daughter's intrusion -- for being such a bother. But Einstein cut her off. He said, "She has not been bothering me! When a child finds such joy in learning, then it is my joy to help her learn! Please don't stop Emmy from coming to me with her school problems. She is welcome in this house anytime." -And that's how it is with God! He is our neighbor, and He wants us to come to His house anytime! (http://frtonyshomilies.com/).

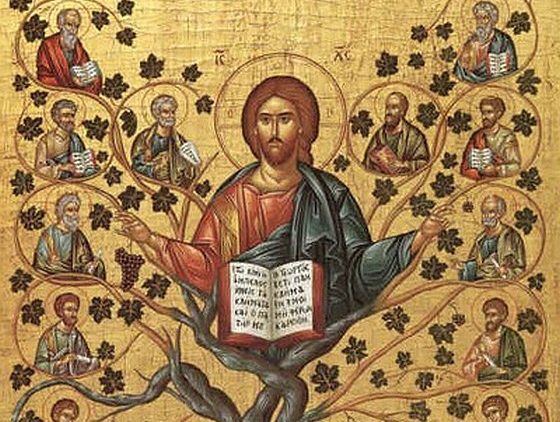

Scripture lessons summarized: The first reading, taken from Deuteronomy, reminds us that God not only gives us His Commandments in Holy Scriptures, but that they are also written in our hearts so that we may obey them and inherit eternal life with God. In the second reading, St. Paul reminds the Colossians, and us, that just as Christ Jesus is the “visible image of the invisible God,” so our neighbors are the visible image of Christ living in our midst. In today’s Gospel, a scribe asks Jesus a very basic religious question: “What should I do to inherit eternal life?” In answer to the question, Jesus directs the scribe’s attention to the Sacred Scriptures. The Scriptural answer is, “love God and express it by loving your neighbor.” However, to the scribe the word “neighbor” means another scribe or Pharisee – never a Samaritan or a Gentile. Hence, the scribe insists on clarification of the word “neighbor.” So, Jesus tells him the parable of the Good Samaritan. The parable clearly indicates that a “neighbor” is anyone who needs help. Thus, the correct approach is not to ask, “Who is my neighbor?” but rather to ask, “Am I a good neighbor to others?” Jesus, the Heavenly Good Samaritan, gives us a final commandment during the Last Supper, “Love one another as I have loved you,” because the invisible God dwells in every human being.

The first reading: Deuteronomy 30:10-14 explained: Jesus told the parable of the Good Samaritan in the course of a discussion about the Law which occurred in the context of Jesus’ fateful journey toward Jerusalem and his coming death. Jesus dared to ask people to go beyond the Law of Moses, and that is one of the things that got him in so much trouble. To prepare us for that lesson, the Church selects from the Hebrew Scriptures a description of the Law that captures its greatness. Today’s passage, taken from the book of Deuteronomy, reminds us that God is not beyond human reach. Pagan religions of Moses’ time taught that God was accessible only through the mediation of specially selected persons who made that contact by acquiring secret knowledge and by performing bizarre rituals or by using hallucinogenic drugs. But God reveals to Moses that His Law is not across the sea or up in the sky -- or locked in a tabernacle! God has written his life-giving and salvific law in the human heart (v. 14; see also Jeremiah 31:33; Ezekiel 36:26-27). This Law is "not in heaven... nor is it beyond the seas," outside our reach. No, "it is very near to you, it is in your mouth and in your heart for your observance." Hence, Moses urges the people of Israel to hear the voice of God from the Law and to keep His Commandments. He tells us that God is very near to us – in the neighbors we shall encounter each day this week. When we act as neighbor to them, we act as neighbor to God Himself.

The second reading: Colossians: 1:15-20 explained: The Christians of Colossae were misled by some false teachers, Gnostics, who saw Jesus as only a man, though just under the angels in rank. They taught that Jesus became Lord and Christ only at his Resurrection. Hence, Paul quotes this early Christian hymn to assure the Colossian Christians of: (1) the primacy of Christ over and above all angels and cosmic powers; (2) the value and necessity of the cross; and (3) the cosmic effects of salvation. This hymn also affirms Christ’s power and position over the four ranks of angels (v. 16: thrones, dominations, principalities and powers) which, according to Hellenistic Judaism, guarded the seven levels of Heaven. It asserts that Jesus is the full revelation of God, and that it is through the person and mission of Jesus that God has reconciled all things in Heaven and on earth to Himself, making peace between us and Him. It is this Jesus who lives in us and in our neighbors.

Gospel exegesis: The context: A scribe asked Jesus a very basic religious question: “What should I do to inherit eternal life?” In answer to the question, Jesus directed the Scribe’s attention to the Sacred Scriptures. The Scriptural answer is “love God and express it by loving your neighbor.” However, to the scribe, the word “neighbor” meant another scribe or Pharisee – never a Samaritan or a Gentile. Hence, the scribe insisted on a clarification of the word “neighbor.” So, Jesus told him the parable of the Good Samaritan. The parable clearly indicates that a “neighbor” is anyone who needs help. Thus, the correct approach is not to ask the question “Who is my neighbor?” but rather to ask, “Am I a good neighbor to others?”

Three philosophies of life: In the parable of the Good Samaritan, Jesus presents three philosophies of life concerning our relationship with our neighbor:

1) The philosophy of the thieves who robbed the Jewish traveler – Lust: “What is yours is mine; I will take it by force.” This has been the philosophy of Marxism and other revolutionary movements and of modern terrorist groups. In accepting this philosophy of life, the thieves, like their modern counterparts, terrorized others and exploited them, ignoring human rights and having selfish gain as their chief motive. In Jesus’ day, the steep, winding, country road from Jerusalem to Jericho was the safe haven for such bandit groups. No wonder, the Jewish traveler was robbed, stripped, beaten and left for dead on the Jericho Road! Some Bible scholars estimate there were at least 12,000 "thieves" in that Judean wilderness surrounding Jerusalem. These thugs roamed the countryside like packs of wild dogs, attacking innocent victims. In our world, many more thieves operate than we might realize. These are the privileged few, the "robber barons" of the modern world. They are the "Enron" executives of every company who just can't be satisfied with being wealthy; they have to have all the marbles. The robber who takes money that does not belong to him is a thief. The rapist who takes sexual pleasure from someone not his spouse is a thief. The adulterer who steals another’s spouse is a thief. Corporate executives and CEOs who bilk innocent stockholders of billions of dollars are thieves. God has given us things to use, and God has given us people to love. But when we begin to love things and use people, we become thieves. If our attitude is: "I just make sure I get mine. I don't care about anyone else," we are probably thieves.

2) The philosophy of life of the Jewish priest and the Levite – Legalism: “What is mine is mine; I won’t part with it.” The priests were powerful upper-class authorities governing the Temple cult. The Levites were the priests’ associates, who provided music, incense, sacred bread, Temple curtains and adornments. Their duties also included “kosher meatpacking” and banking. In the parable, the representatives of these classes did not pay any attention to the wounded man because of their utter selfishness. Misplaced zeal for their religious duty gave them a couple of lame excuses: a)” If the man is dead and we touch him we will be unclean for seven days (Numbers 19:11) and disqualified from Temple service.” Thus, they saw the wounded man on the road, not as a person needing help, but a possible source of ritual impurity. b) “This may be a trap set for us, by hiding bandits.” [This excuse has some validity, as bandits sometimes did use a “wounded” member to decoy a prospective victim into stopping, thus setting himself up for robbery.] The parable's priest and Levite, however, represent people who are always demanding their rights, but never talking about their responsibilities. These two men exercised their legal right to pass this man by, and forgot God in the process. These people don't say, "I do what I want to do," but, "I will only do what I have to do-I won't stick my neck out for anybody." When one only does what one must do in life, one is not a good neighbor.

3) The philosophy of the Samaritan -- Love: “What is mine is yours as well. I shall share it with you.” The Samaritan was generous enough to see the wounded Jew as a neighbor. He ignored the long history of enmity between his people and the Jews.

[The Samaritans were a bastard race by Judean standards. They presumably originated from the Israelites who remained behind in their homeland when the Assyrians, following their conquest in 722 BC, deported the leading families of the region. In the years that followed, the Israelites who remained intermarried with the foreign settlers brought in by the Assyrians. The new hybrid ethnic generation -- "Jewish Assyrians"—continued to regard the Torah as their law but erected their own temple on Mount Gerizim, just outside Shechem (modern Nablus), at a time when there was no Temple in Jerusalem. The hostility between Jews and Samaritans was worsened by a deep-rooted rivalry concerning their sanctuaries (Mt. Gerizim, Mt. Zion), messianic expectations, and by disputes regarding the interpretation of their sacred texts. John Hyracanus, a Maccabaean Jewish ruler, destroyed this Shechem temple during his reign (134-104 BC), and thus created lasting enmity between the Judeans and the Samaritans. No wonder, every morning in his daily prayer a Pharisee would go to the Temple and, out loud, thank God he had not been born a woman, a Gentile, or a Samaritan. Yet, Jesus makes the Samaritan the hero of the story.]

The Good Samaritan was taking a real risk, since the robbers who had assaulted the traveler might still be nearby. Nevertheless, he gave first aid to the wounded Jew, took him to a nearby inn and made arrangements for his food and accommodation by giving the innkeeper two denarii. Two denarii was a lot of money—enough, in fact, to pay for more than three weeks’ board and lodging. The Samaritan also assured the innkeeper of further payment for any additional medical requirements of the wounded man. What made this Samaritan so special was not the color of his skin, but the compassion in his heart. No law could make the priest, or the Levite stop, but love could make the Samaritan stop. Who would we have been that day -- the thief, the priest, the Levite, or the Good Samaritan?" If a person has a need that we can and should meet, that person is our neighbor. Every time we see a person in need, we immediately become a neighbor; we become a minister with a ministry. Columnist Ann Landers once wrote, "Be kind to people. The world needs kindness so much. You never know what sort of battles other people are fighting. Often just a soft word or a warm compliment can be immensely supportive. You can do a great deal of good by just being considerate, by extending a little friendship, going out of your way to do just one nice thing, or saying one good word." Mark Twain once wrote, "Kindness is a language that the deaf can hear and the blind can read."

Life messages: 1) We need to remember that the road from Jerusalem to Jericho passes right through our home, parish, school and workplace. The Jericho Road is any place where people are being robbed of their dignity, their material goods or their value as human beings. It is any place where there is suffering and oppression. As a matter of fact, the Jericho Road may be our own home, the place where we are taking care of a mother or father, husband or wife, or even our own children. We may find our spouse, children or parents lying “wounded” by bitter words, scathing criticism or other, more blatant forms of verbal, emotional or physical abuse. Hence, Jesus invites us to have hearts of love. What God wants more than anything is for us to show our love to others, in our own home and school, in the workplace, and in the neighborhood, as the Good Samaritan did. Jesus is inviting us to have hearts of mercy for those who are being left hurt or mistreated on any of the “Jericho Roads” of life.

2) Are we good neighbors? A good neighbor does not say, "I do what I want to do," or even, "I do what I have to do," but, "I do what I ought to do." The lawyer’s question— “Who is my neighbor?”—reveals that he was really self-centered. The parable makes us realize that every human person is our neighbor. How have we been good neighbors this week? To whom did we behave in a neighborly way? The parable is a condemnation of our non-involvement as well as an invitation for us to be merciful and kind to those in need, including those in our family, school, neighborhood, and parish. We are invited to be people of generosity, kindness, and mercy toward all who are suffering. A sincere smile, a cheery greeting, an encouraging word of appreciation, a heartfelt “thank you” can work wonders for a suffering soul. Within every society, there is fear of those who are "different," who differ from us in religion, skin-color, dress or language. The parable invites us to make them neighbors. Why? Because "one’s neighbor is the living image of God the Father, redeemed by the blood of Jesus Christ, and placed under the permanent action of the Holy Spirit. One’s neighbor must therefore be loved, even if he or she is an enemy, with the same love with which the Lord loves him or her.” (Pope St. John Paul II, Sollicitudo Rei Socialis, 1987).

3) We need to allow the “Good Samaritans” touch our lives. Do you recall the consternation and shock in so many areas years ago when PLO leader Yasser Arafat and Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin shook hands for the whole world to see? People from both Arafat's and Rabin's cultures were shocked by it and condemned that handshake! Let us be willing to touch and be touched by persons we have once despised. For some of us, these may be persons of another color or race; for others, these may be persons of a different political persuasion. For still others these may be former enemies who have hurt them, abused them or offended them. Let us pray that the Spirit of the living God may melt us, mold us and use us so that there will no longer be even one person who is untouchable or outside the boundaries of our compassion.

4) We are commanded to be loving and merciful to our enemies. "Enemies" include both people we hate, and those who hate us. The Jews and the Samaritans during the time of Jesus hated each other. When Jesus told the story of a Samaritan helping a Jew, everyone was probably shocked. A Samaritan outcast helping a Jew? Impossible! “Good Samaritan” would have sounded like a bad joke—a contradiction in terms. The parable was an invitation for Jews to love Samaritans and Samaritans to love Jews. It is an invitation for people of all times to love their enemies -- to love those they have previously hated. (Fr. Antony Kadavil).

Thank you for reading our article. You can keep up-to-date by subscribing to our daily newsletter. Just click here