De Foucauld: Total surrender to God and universal fraternity

By Thaddeus Jones

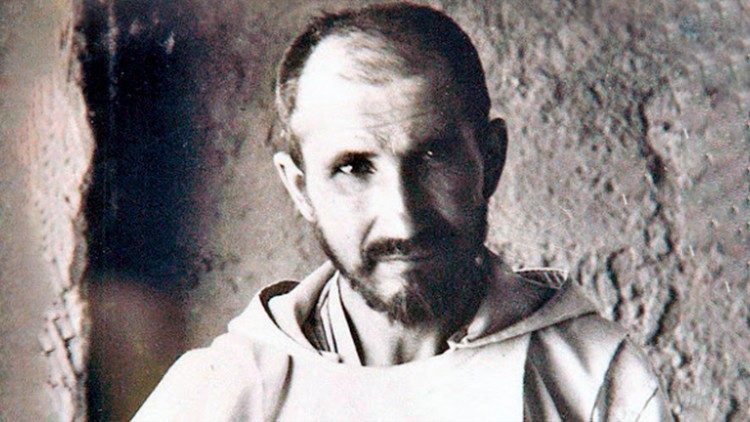

On Sunday, Pope Francis presides over a morning Mass with the canonization of ten Blesseds, including Fr. Charles de Foucauld (1858-1916).

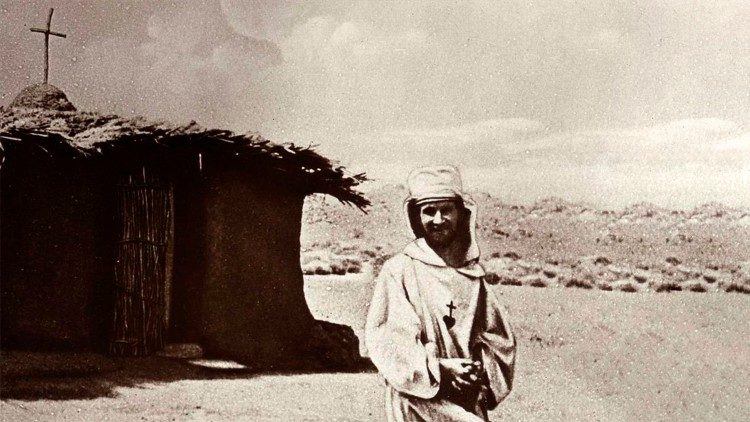

His life was one marked by transformation: he served as a soldier, then an explorer, had a conversion experience and became a monk, and finally a desert hermit, serving most of his years among the Tuareg people of Algeria.

De Foucauld is considered to be one of the pioneers of interreligious dialogue. He witnessed to his faith above all through his quiet example, without words, of trying to live it through deep prayer and friendship and service to the people he came to know. His life and faith witness could easily make him a model for "human fraternity" that Pope Francis has so often mentioned in his writings and talks.

The Pope has called attention to Charles de Foucauld for his quiet, personal witness to faith and human fraternity among the people he served during his life as a simple hermit, priest, and friend in the expanses of the Sahara desert. At the end of his encyclical Fratelli tutti, the Pope wrote:

Little Sister Claire Nicole is a member of the women's religious congregation inspired by the witness of Charles de Foucauld and the archivist at their Rome-based headquarters.

In an interview with Vatican News, Sister Claire describes how de Foucauld is a model for living and witnessing to human fraternity.

Q: To begin, please tell me a bit about your own congregation and how it's inspired by the example and life of Charles de Foucauld.

I will start the other way around. Charles de Foucauld all his life hoped that some brothers or sister would come and live with him. Brothers. And he was killed in 1916. Alone. He remained alone. No one came with him. So what happened? 1921, a biography was written and many people read this, and from that point different groups started. First, the little brothers of Jesus and then other groups. And then we our group started officially starting date is 1939. So that Charles is our inspiration. He's not our founder. But all what we live is like trying to copy him like he's a model for us.

Q: What parts of the world are you present?

So we are present in Europe, in Africa and in Asia. There is a small group in Australia and then also a group in North and South America. So quite spread out all over the world. But we are small groups, always small groups. Now more or less altogether. We are a little more than 900 sisters.

Q: Talking about the canonization coming up on Sunday. What does that mean for you and you as a group?

For us as a group, I think we all knew since long time that he was a remarkable man. We could call him a saint. But what is new is that now a lot of people start talking about him or a lot of journalists came and ask so that I think he will be better known or people that never heard about him will know about him. For me, that's the main point that he will be for more people a model.

Q: And tell me about blessed and soon to be Saint Charles de Foucauld. What aspects of his life and his witness strike you most.

For me? What is the most important in this man is that he was a good man and everybody knew how good he was. When I read what is in his biography or when I read what he writes, all the contacts he had with the people who lived next to him, it is very striking. I will tell one story. In Algeria at that time it was a French colony or a French country. They were soldiers, French soldiers, and they were the officers who were French and then other soldiers who were from this country. And one time at New Year's Eve, the soldiers, the officers were away to have their party. And in the camp, only the small soldiers were there and they wanted to have fun. So, they put gunpowder in a gun. And they wanted to make firecrackers, I don't know what. Anyway, it exploded and this soldier was had a very bad wound on his hand. Instead of calling the military doctor, they went to get Charles and ask him to take care of this wounded man. This wounded man many years later said, I asked him because I knew he was so good. Even he was not a doctor. But for him it was more important because he was so good. For me, that's the most important in this man. He was good and he tells us the most important is the goodness that comes out of everyone. It is not what we talk, it is not what we say. It is to be good because God is good.

Q: About also living among the native peoples, especially Algeria. What was his living ministry like then?

I think there is an evolution, what he thought when he went there and when he arrived and what we see, what he's living in the last years is different. He changed his mind. I think he went and he had a very strong experience of the love of God, and he wanted to bring that to other people. He said he supposed they didn't know about that. Maybe they did, but anyway, not the way he thought. So that was his first idea when he arrived. But then several things happened. One is that after a few years, he got sick because he did not eat enough. And also there was drought. So he was giving everything he had to eat. And he got sick. And his neighbors, they went to look for goats and brought him some milk. And so he did not die. Otherwise, he would have died. And I think he realized he thought he was the one who was bringing them something. But in fact, they saved him. He wanted to bring the Savior, but they saved him. And probably this has been a very deep experience. From that point on, he understood all human beings are equal, we are human. And what is important is how we live and how we love each other. It is not to which church or to which religion we belong.

Q: And his going to Algeria, what was his thinking in going there and living almost like a hermit among the people?

When he was young, he made exploration in Morocco. At that time Morocco was closed for European people. It was forbidden to go there. So he first went to a place very close to the Moroccan border, and his dream was to enter there again. But this did not happen. And then he thought he would stay where he was for his whole life. But then some former friends, French officer, invited him to go more south, and he thought that's the unique chance. And he went and then he lived there because his idea was to go always further and further. Like Pope Francis, says now to the periphery. That's exactly what he did. Always far away, far away to meet these people. And well, what happened at the end? He was friends with them. I don't think it was what he had planned, but at the end that was what happened.

Q: He was also moved very much by the culture, wasn't he? He collected poetry of Tuaregs and also documented the language as well, didn't he?

Because he thought, if I want to, to be close to those people, I have to know their language. And so, he studied for at least 12 years, and he wrote a very big dictionary, four volumes, which is, in fact, more than a dictionary. It's like an encyclopedia about their lives. And until to today, there is no other book that is so good as his book. So he wanted to be able to talk correctly to them. So he studied. And by the end, the people say he knows our language better than we do. So, all this linguistic work is in order to be close.

Q: Could you say in some ways he was evangelized by the people themselves as much as perhaps his idea as well was witnessing in a quiet way to his own faith?

Yes, I think I think when we read the document of Vatican II, there is some place where it says that the Holy Spirit is always going before us, wherever. And that's what happened to him. And certainly he, through the people he met, he made he knew God better. Certainly.

Q: Would you say he was a bridge as well between cultures and faiths, meaning building a bridge of understanding and getting to know each other?

Yes, this is very clear. The fact of learning their culture was in order to understand better, to know them better, because if you are a friend with someone, you want to know how we live, how he speaks, what he likes, what he knows. It is not a bridge. It is friendship. Friendship that make him do all this.

Q: Pope Francis often speaks today about human fraternity. A need to get to know each other, especially people of other faiths, other traditions, other cultures. How would you say Charles de Foucauld in some ways is an example, a model for that today of human fraternity.

He is a model. I think he was not conscious of that. When he learned theology, certainly, he never learned about that. But in practice in his daily life that is what happened, he is a model of human fraternity. And he says, I want everybody to consider me as their brother and he even say the Muslims, the Jews, the atheists, I would like them all to know I am their brother. And he said I would like them, or that they call my house fraternity, in the sense my house is the house for all my brothers and sisters.

Q: What would you say human fraternity was for de Foucauld in terms of his own life and his own ministry?

I think human fraternity is his only goal. He had no other goal than be a brother for everybody. So that's human fraternity. Everybody, no matter who you are, Muslim, Christian, nonbeliever. For him, I think there was no difference. They were all human beings, so they were all brothers and sisters. And he really tried to be close to them, to to love them.

Q: And his emphasis was more on being and less on words.

He would say: do not talk, do not preach, but be good. And you can be good if you are related he says to Christ, to Christ that dwells in you. But all this all this is a silent process. You are not going to go outside and shout, I am related to Christ, but it should be shown or people should see that in the way you live, in the way you act. But there are no words.

Q: I imagine also because the colonial past, he was in a sense, different. He wasn't there going with strategic, economic interests, but he was going there simply to witness to who he is, what he believes to the most remote peoples.

Yes. If you read what he wrote, you can see different things. But at some point, he is very angry with the French government, let's say, because he said if you continue to go there only to make money, you are not faithful to what you should be, because he thinks in terms of France is the daughter of the Church. And he said, if you really want to be a Christian, if you want to as a country, because that's what he what he thought at that time, witness something from Christian faith, that's not the way you should go. Because he said people come there and they sell guns and they sell alcohol. He said, that's not the way you should act.

Q: If anyone were interested in reading more about Charles de Foucauld, what would you recommend?

I think they should read the biography of Pierre Sourisseau because many people, they read his spiritual writings. That's what he wrote when he was younger, when he was living alone in Nazareth. That was like a big retreat. But I think we should look first at his life, not at his writings, because his life is talking much more than certain things that he wrote. And also what he wrote in his meditation, it was for himself. He never thought it would be published, but I think his life talks a lot.

Q: Could you say that the witness of Charles de Foucauld also helps us see today how getting to know the other person who may be of a different faith, a different culture, can help do away with our fears, perhaps, that might be there of the unknown.

It is obvious he is the model. He is model for this way he because he said I want to be good. And so if you give, if you show to someone that you appreciate him, this is the way to get to friendship and to get to human fraternity. There is no other way because also if you get close to this other person, probably it might happen that this other person is getting close to you and you walk away together. And this is how fraternity comes to exist. There is no other way.

Q: In some ways, it's just simply a dialogue of life, isn't it?

Yes, it is a dialogue all life. And if you read his biography or if you read what he wrote in the last years of his life in a book called Carnet, every day he would write just a few sentences when he says who he met, who was sick, who died. You see, this is a model of human fraternity. For instance, in this Carnet, he wrote my neighbor - and then there is the name of this woman - had a miscarriage. He writes this in his notes. So it means he was so close to that person and he knows maybe this woman did suffer. But for him, it is important. My neighbor had a miscarriage.

Q: Could you say if there were more of this happening, getting to know each other, there'd be more peace in the world?

Sure. It is so obvious. Yes, sure.

Thank you for reading our article. You can keep up-to-date by subscribing to our daily newsletter. Just click here