Woman and authority as depicted on 4th century Christian sarcophagi

By Christine Schenk CSJ

Because most of history relies on literary records authored by men, discovering reliable historical data about early Christian women can be challenging. Christianity relies heavily on the written word as a primary means of understanding its history.

As Dr. Janet Tulloch attests in an article published in 2004, information gleaned from visual artifacts such as frescos, paintings, and sarcophagus friezes has, until recently, been left almost exclusively to art historians and archaeologists.

Although many female patrons financially subsidized men in the early Church (Mary of Magdala, Phoebe, Lydia, Paula, Olympias), their presence is barely discernible in literary sources. For some time now, scholars have understood that archaeology is an important source of information about early Christian women.

Written vs archeological record

For the first four centuries of Christian history (and even today) churchmen justified curtailing female authority by repeating 1 Timothy’s admonishment that women be silent in the assembly and not teach or have authority over men (2:12).

Yet Christian funerary art from the late third to the early fifth centuries depicts women both teaching and preaching. Only a brief discussion of this fascinating topic is possible here.

For both Christian and pagan Romans, a sarcophagus was not just a container for a corpse, but a monument filled with meaning. Roman funerary art was meant to construct the identity of the deceased person and commemorate their values and virtues.

Only the wealthy could afford such an expensive tomb, and planning how one wished to be remembered was an important process. Being portrayed with a scroll, capsa (basket for scrolls) or codex (book) was an instant indicator of the deceased’s learning, status, and wealth.

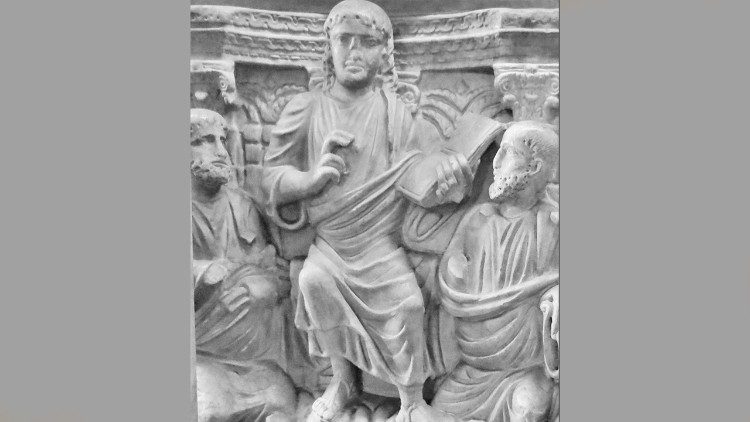

Both Christian women and men were commemorated and idealized as persons of status, authority, learnedness, and religious devotion. When the deceased’s funerary portrait was depicted with a scroll or capsa in close proximity to biblical scenes, it also signaled learnedness about the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures (Figure 1).

Over a three-year period, I analyzed 2,119 images and descriptors of 3rd to early 5th-century sarcophagi and fragments, comprising all publicly available images of Christian sarcophagi. An in-depth analysis of selected iconographical motifs found that many early Christian women were commemorated as persons of status, influence, and authority within their communities.

One highly significant finding is that there are three times as many solo funerary portraits of Christian women compared to Christian men. The likelihood is less than 1 in 1000 that this finding is due to chance.

Many sarcophagus reliefs portray deceased women surrounded by biblical scenes, with their hands in a speech gesture, and holding scrolls or codices. These offer poignant witness that 4th century women did not heed admonitions to be silent.

Their prevalence suggests the emergence of a new female identity of biblical learnedness and teaching authority. Another significant finding is that female portraits were statistically twice as likely to be flanked by “apostle” figures (often Peter and Paul) probably to validate their religious authority (Figures 2, 3, 4).

What the archeological record tells us

Early Christian sarcophagus iconography suggests that female Christians were learned, pious, and wealthy. Judging from the number of solo female sarcophagi, they were also single women or widows, evoking the early communities of widows and virgins discussed in the first article in this series.

Since many are depicted with scrolls and speech gestures in the midst of biblical scenes, we can posit that they were well versed in Scripture and wished to be represented as women with faith in God’s power to save and as teachers about Jesus’s life and healing miracles. Their communities idealized them as learned figures with authority to, at the very least, proclaim and teach Scripture.

It is plausible that later Roman “mothers of the church,” such as Marcella, Paula, Melania the Elder, and Proba, admired these early female role models who inspired them to love and learn about Scripture.

Literary sources about “church mothers,” are consistent with the archaeological findings, confirming what contemporary scholars –including Pope Benedict XVI—had previously theorized: women were considerably more influential in early Christianity than is generally recognized.

While men predominate in the literary record, archaeological funerary portraits point to a preponderance of Christian women remembered as exercising substantial ecclesial authority within their communities. As we shall see, the women who gathered around our “church mothers” developed into some of our earliest intentional communities of women religious.

A more detailed treatment of the 3-year study conducted by Christine Schenk on 3rd to early 5th-century sarcophagi and fragments, can be found in the author’s book entitled Crispina and Her Sisters: Women and Authority in Early Christianity (Fortress Press, 2017). Look for the third article in the series portraying prominent 4th century Christian women who founded monasteries, laying the foundation for the life now lived by women religious.

Thank you for reading our article. You can keep up-to-date by subscribing to our daily newsletter. Just click here