Church marks 60th anniversary of Pope Paul VI’s ‘Ecclesiam suam’

By Vatican News

Sixty years have passed since August 5, 1964, when Pope Paul VI, a little more than a year after his election as Bishop of Rome, announced the publication of Ecclesiam suam during the General Audience at Castel Gandolfo.

“We will share something with you… we have finally finished writing our first encyclical letter, which will bear the date of the feast of the Transfiguration of Christ, tomorrow, 6 August; and the Latin text will begin with the words ‘Ecclesiam suam’ which will serve to identify it. It will be published, we hope, in the coming week.”

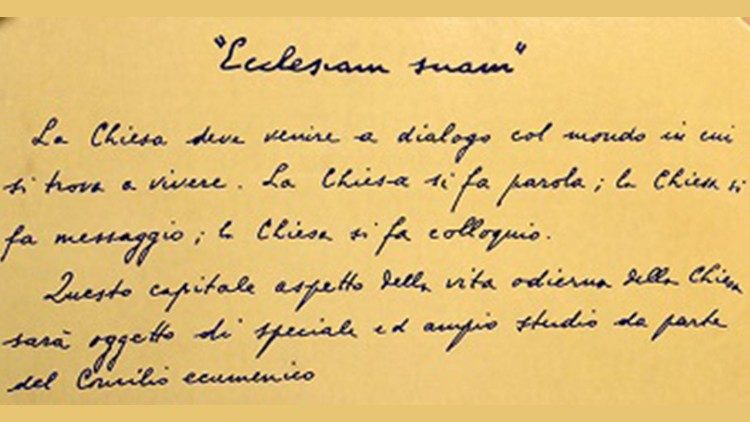

The programmatic document of Giovanni Battista Montini was thus signed on the same day of the year as the Pope’s death fourteen years later. The text was entirely handwritten by the Pope.

Church’s understanding of herself

The encyclical sets out to make clear “to all men the Church’s importance for the salvation of mankind, and her heartfelt desire that Church and mankind should meet each other and should come to now and love each other.”

The Church “sees clearly enough the astounding newness of modern times, but with frank confidence it stands upon the path of history and says to men: ‘I have that for which you search, that which you lack’.” The text of the letter is not intended to have a “a solemn and strictly doctrinal function,” Pope Paul explains, “but merely to communicate a fraternal and informal message,” focused on three main ideas.

The first concerns the need for the Church to “deepen its consciousness of itself.” This leads to the second thought, concerning the necessity “of correcting the defects of its own members, and of leading them to greater perfection” and the importance of finding “the way to achieve wisely so sweeping a renovation.” Paul VI urges bishops “to find greater courage to undertake the necessary reforms, but also to secure from your collaboration both advice and support in so delicate and difficult an undertaking.”

Paul’s third thought concerns “the relationships which the Church of today should establish with the world which surrounds it and in which it lives and labours.” This is the great theme of dialogue between the Church and the modern world, the “urgency” of which is “such as to create a burden” in the Pope’s soul, indeed almost “a vocation.”

The risk of worldliness

“It is known to all,” we read in Ecclesiam suam, “that the Church has her roots deep in mankind, that she is part of it, that she draws her members from it, that she receives from it precious treasures of culture, that she suffers from its historical vicissitudes, that she favors its progress. Now, it is likewise known that at present mankind is undergoing great transformations, upheavals, and the developments which are profoundly changing not only its exterior modes of life but also its ways of thinking.”

“All of this, like the waves of an ocean,” the Pope explains, “envelopes and agitates the Church itself. Men committed to the Church are greatly influenced by the climate of the world; so much so that a danger bordering almost on vertiginous confusion and bewilderment can shake the Church’s very foundations and lead men to embrace most bizarre ways of thinking, as though the Church should disavow herself and take up the very latest and untried ways of life.”

“The first benefit to be reaped from a deepened awareness of herself by the Church,” Paul VI explains, “is a renewed discovery of her vital bond of union with Christ.”

Christianity’s encounters with modern culture

The encyclical proceeds by reaffirming the need for Christianity to engage with modern culture.

“This imminent contact of the Church with temporal society continually creates for her a problematic situation, which today has become extremely difficult. On the one hand Christian life, as defended and promoted by the Church, must always take great care lest it should be deceived, profaned or stifled as it must strive to render itself immune from the contagion of error and of evil,” the Pope says.

“On the other hand, Christian life should not only be adapted to the forms of thought and custom which the temporal environment offers and imposes on her, provided they are compatible with the basic exigencies of her religious and moral program, but it should also try to draw close to them, to purify them, to ennoble them, to vivify and to sanctify them.”

The contours of the reform

The Pope goes on to clarify the contours of the reform, specifying that “this reform cannot concern either the essential conception of the Catholic Church or its basic structure,” and noting that “we would be putting the word ‘reform’ to the wrong use if we were to employ it in that sense.”

“Let us not deceive ourselves into thinking that the edifice of the Church which has now become large and majestic for the glory of God as His magnificent temple, should be reduced to its early minimal proportions as if they alone were true and good,” Pope Paul warns. “Nor should we be fascinated by the desire of renewing the structure of the Church through the charismatic way…”

Paul VI also cautions us against the idea that reform consists in conforming to the world.

“We must deepen within us these convictions if we are to avoid the other danger which the desire for reform can produce… in the many faithful who think that the reform of the Church should consist primarily in adapting its sentiments and habits to those of the world. The fascination of worldly life today is very powerful indeed. Conformity appears to many as an inescapable and wise course. Those who are not well rooted in Faith and in the observance of Ecclesiastical Law easily think that the time has come for concessions to be made to secular norms of life, as if these were better and as if the Christian can and must make them his own.”

The threat of relativism

Already in his first encyclical, Pope Paul highlights the threat of relativism: “Naturalism threatens to render null and void the original conception of Christianity. Relativism, which justifies everything and treats all things as of equal value, assails the absolute character of Christian principles… Sometimes even the apostolic desire of approaching the secular milieu or of making oneself acceptable to modern mentality, especially that of youth, leads up to a rejection of the forms proper to Christian life and even of its very dignity, which must give meaning and strength to this eagerness for approach and educative influence. Is it not perhaps true that often the young clergy or indeed even some zealous Religious moved by the good intention of penetrating the masses or particular groups, tend to get mixed up with them instead of remaining apart, thus sacrificing the true efficacy of their apostolate to some sort of useless imitation?”

‘Aggiornamento’

Paul VI then takes up the theme of “aggiornamento,” (“updating”), explaining that perfection does not consist “in remaining changeless as regards external forms which the Church through many centuries has assumed. Nor does it consist in being stubbornly opposed to those new forms and habits which are commonly regarded as acceptable and suited to the character of our times. The word ‘aggiornamento,’ rendered famous by our predecessor of happy memory, John XXIII, should always be kept in mind as our program of action.”

However, the Pope warns again – showing his evident concern on this point – “The Church will rediscover her renewed youthfulness not so much by changing her exterior laws as by interiorly assimilating her true spirit of obedience to Christ and accordingly by observing those laws which the Church prescribes for herself with the intention of following Christ.”

With regard to “the general lines of the renewal of ecclesiastical life,” Pope Paul emphasizes two particular points, calling the Church to embrace “the spirit of poverty” and “the spirit of charity.”

The duty of evangelization

Ecclesiam suam then addresses the issue of dialogue with the world. “If the Church acquires an ever-growing awareness of itself, and if the Church tries to model itself on the ideal which Christ proposes to it, the result is that the Church becomes radically different from the human environment in which it, of course, lives or which it approaches.”

But this distinction between the Church and the world “is not a separation,” Paul VI explains. “Neither is it indifference or fear or contempt. When the Church distinguishes itself from human nature, it does not oppose itself to human nature, but rather unites itself to it.”

The Church “does not make an exclusive privilege of the mercy which the divine goodness has shown it, nor does it distort its own good fortune into a reason for disinterest in those who have not shared it. Rather in its own salvation it finds an argument for interest in and for love for anyone who is either close to it and can at least be approached through universal effort to share its blessings.”

Pope Paul VI understands dialogue as a result of “a need for outpouring… the duty of evangelization”: “It is the missionary mandate. It is the apostolic commission.”

“An attitude of preservation of the faith is insufficient… The Church should enter into dialogue with the world in which it exists and labours. The Church has something to say, the Church has a message to deliver; the Church has a communication to offer;” because “even before converting the world, nay, in order to convert it, we must meet the world and talk to it.”

Dialogue is not imposition

Paul VI calls Jesus’ mission a “dialogue of salvation,” a dialogue that “did not physically force anyone to accept it; it was a tremendous appeal of love which, although placing a vast responsibility on those toward whom it was directed, nevertheless left them free to respond to it or to reject it.”

“This type of relationship indicates a proposal of courteous esteem, of understanding and of goodness on the part of the one who inaugurates the dialogue,” the Pope explains further. “It excludes the a priori condemnation, the offensive and time-worn polemic and emptiness of useless conversation. If this approach does not aim at effecting the immediate conversion of the interlocutor, inasmuch as it respects both his dignity and his freedom, nevertheless it does aim at helping him, and tries to dispose him for a fuller sharing of sentiments and convictions.”

Dialogue, the Pope writes, presupposes “a state of mind… of one who realizes that he can no longer separate his own salvation from the endeavour to save others.” Dialogue “is not proud, it is not bitter, it is not offensive. Its authority is intrinsic to the truth it explains, to the charity it communicates, to the example it proposes; it is not a command, it is not an imposition. It is peaceful; it avoids violent methods; it is patient; it is generous.” It is “the union of truth and charity, of understanding and love is achieved.”

World not saved from outside

The world, Paul VI insists, admirably summarizing the Church’s closeness to all, “cannot be saved from outside. As the Word of God became man, so must a man to a certain degree identify himself with the forms of life of those to whom he wishes to bring the message of Christ. Without invoking privileges which would but widen the separation, without employing unintelligible terminology, he must share the common way of life — provided that it is human and honorable — especially of the most humble, if he wishes to be listened to and understood. And before speaking, it is necessary to listen, not only to a man’s voice, but to his heart. A man must first be understood; and, where he merits it, agreed with.”

But the Pope warns once more of the dangers that make “the apostle’s art a risky one,” recalling that “the desire to come together as brothers must not lead to a watering down or subtracting from the truth. Our dialogue must not weaken our attachment to our faith. In our apostolate we cannot make vague compromises about the principles of faith and action on which our profession of Christianity is based. An immoderate desire to make peace and sink differences at all costs is, fundamentally, a kind of scepticism about the power and content of the Word of God which we desire to preach. Only those who are completely faithful to the teaching of Christ can be an apostle.”

Atheism

Paul VI then considers the recipients of missionary dialogue in terms of “three concentric circles.” The first is consists of “all people of good will,” because “there is no one who is a stranger to [the Church’s] heart, no one in whom its ministry has no interest. It has no enemies, except those who wish to be such.”

“We realize, however, that in this limitless circle there are many — very many, unfortunately — who profess no religion,” the Pope continues, introducing the theme of atheism. “We are aware also that there are many who profess themselves, in various ways, to be atheists. We know that some of these proclaim their godlessness openly and uphold it as a program of human education and political conduct, in the ingenuous but fatal belief that they are setting men free from false and outworn notions about life and the world and are, they claim, putting in their place a scientific conception that is in conformity with the needs of modern progress.”

Atheism “is the most serious problem of our time,” the Pope says, adding, “We are firmly convinced that the theory on which the denial of God is based is utterly erroneous. This theory is not in keeping with the basic, undeniable requirements of thought. It deprives the reasonable order of the world of its genuine foundation.”

Communism and the Church of Silence

Paul VI then explicitly brings up Communism and the persecution of Christians, recalling the reasons “that compel us, as they compelled our predecessors and, with them, everyone who has religious values at heart, to condemn the ideological systems which deny God and oppress the church-systems which are often identified with economic, social and political regimes, amongst which atheistic communism is the chief… Our regret is, in reality, more sorrow for a victim than the sentence of a judge.” He gives the example of the “Church of Silence” that “speaks only by sufferings.”

But the Pope also tries “to seek in the heart of the modern atheist the motives of his turmoil and denial,” noting “his motives are many and complex, so that we must examine them with care if we are to answer them effectively.”

At the same time, Paul VI, recalls the words of his predecessor, John XXIII, who said that although the “the doctrines of such movements, once elaborated and defined, remain always the same,” “the movements themselves cannot help but evolve and undergo changes, even of a profound nature” and adds, “We do not despair that they may one day be able to enter into a more positive dialogue with the Church than the present one which we now of necessity deplore and lament.”

The Pope also dedicates a passage to “a cherished desire” for assisting the cause of “a free and honourable peace” among human beings, a peace that excludes “pretence, rivalry, deceit and betrayal. It cannot do other than condemn, as a crime and destruction, wars of aggression, conquest or domination.”

Believers in the one God

The second of the circles drawn by Pope Paul “made up of those who above all adore the one, Supreme God whom we too adore.”

“Obviously, the Pope says, “we cannot share in these various forms of religion nor can we remain indifferent to the fact that each of them, in its own way, should regard itself as being the equal of any other… Indeed, honesty compels us to declare openly our conviction that there is but one true religion, the religion of Christianity.”

But, after reaffirming faith in the salvific unicity of Jesus, Paul VI says “we do, nevertheless, recognize and respect the moral and spiritual values of the various non-Christian religions, and we desire to join with them in promoting and defending common ideals of religious liberty, human brotherhood, good culture, social welfare and civil order.”

Other Christians

The third circle, finally, concerns dialogue with Christians of other denominations. The Pope insists, in this regard, that “on many points of difference regarding tradition, spirituality, canon law, and worship, we are ready to study how we can satisfy the legitimate desires of our Christian brothers, still separated from us. It is our dearest wish to embrace them in a perfect union of faith and charity.”

Here, too, however, Paul VI draws precise boundaries: “But we must add that it is not in our power to compromise with the integrity of the faith or the requirements of charity. We foresee that this will cause misgiving and opposition, but now that the Catholic Church has taken the initiative in restoring the unity of Christ’s fold, it will not cease to go forward with all patience and consideration.”

The Primacy of Peter

A concluding passage is devoted to the primacy of Peter, with Paul noting with sorrow that some Christians say “if it were not for the primacy of the Pope, the reunion of the separated churches with the Catholic Church would be easy.”

“We beg the separated brethren to consider the inconsistency of this position,” the Pope says, “not only in that, without the Pope the Catholic Church would no longer be Catholic, but also because, without the supreme, efficacious and decisive pastoral office of Peter the unity of the Church of Christ would utterly collapse.”

“It would be vain to look for other principles of unity in place of the one established by Christ Himself,” the Pope says, adding, “We should also like to observe that this fundamental principle of Holy Church has not as its objective a supremacy of spiritual pride and human domination. It is a primacy of service, of ministration, of love. It is not empty rhetoric which confers upon the Vicar of Christ the title of ‘Servant of the Servants of God’.”

Echoing Mystici Corporis Christi

Finally, it should be noted that Paul VI's programmatic encyclical depends profoundly, theologically, on Pius XII’s encyclical Mystici Corporis Christi, on the Church as the Mystical Body of Christ.

In Ecclesiam suam, Paul VI quotes two significant passages in full, one of which insists that “we must see Christ in the Church.”

Pius XII’s encyclical is also echoed in many of the assertions contained in Ecclesiam suam, such as the affirmation that the Church corresponds to the branches of which Christ is the vine; and that “mystery of the Church is not a mere object of theological knowledge; it is something to be lived, something that the faithful soul can have a kind of connatural experience of, even before arriving at a clear notion of it.”

Thank you for reading our article. You can keep up-to-date by subscribing to our daily newsletter. Just click here