At the origins of the museum

By Paolo Ondarza – Vatican City

A hidden, underground treasure. This is how the story of the Vatican Museums begins. Originally a private collection, a place in which the Renaissance popes would delight their guests, today it is a place that is vital for research and culture, its doors open to the world.

The Laocoön and the winemakers

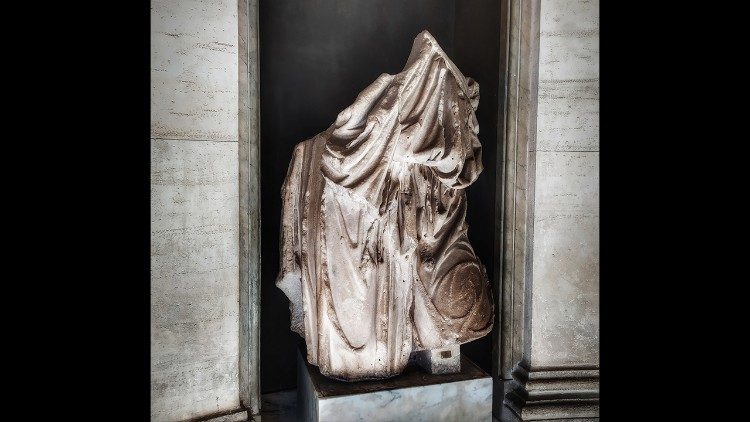

It is January 10, 1506. The spade of the laborers working in the vineyard of Felice De Fredis on the Colle Oppio hits something. They unearthed an imposing marble piece that both scholars and artists immediately identified as Laocoön, described in the second half of the 1st century A.D. by Pliny the Elder as being “in Titi imperatoris domo” (in the palace of the Emperor Titus). The Pope at the time, Pope Julius II Della Rovere, without hesitation, welcomed the advice of Michaelangelo and Giuliano da Sangallo and acquired that incredible marble piece. He saw in it a powerful instrument with which to demonstrate to the world the continuity between his pontificate and the greatness of Pagan Rome.

Heirs of pagan Rome

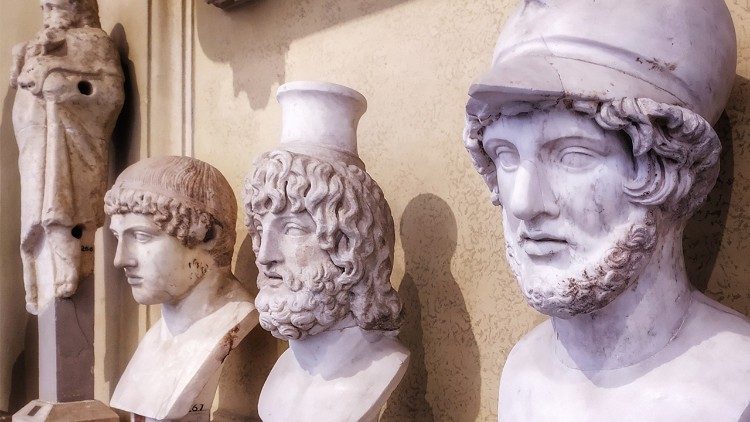

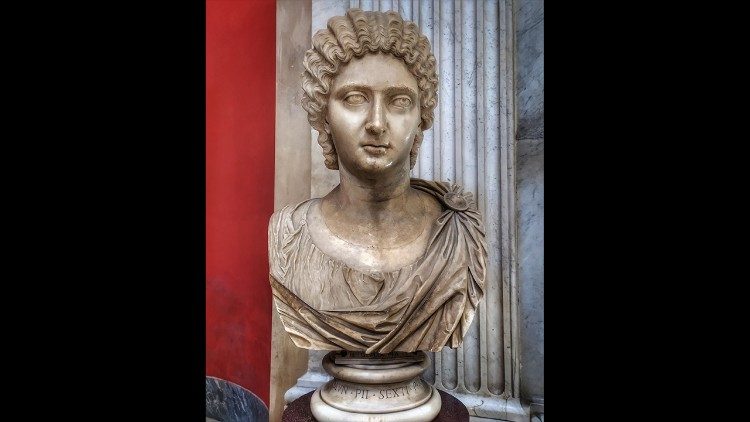

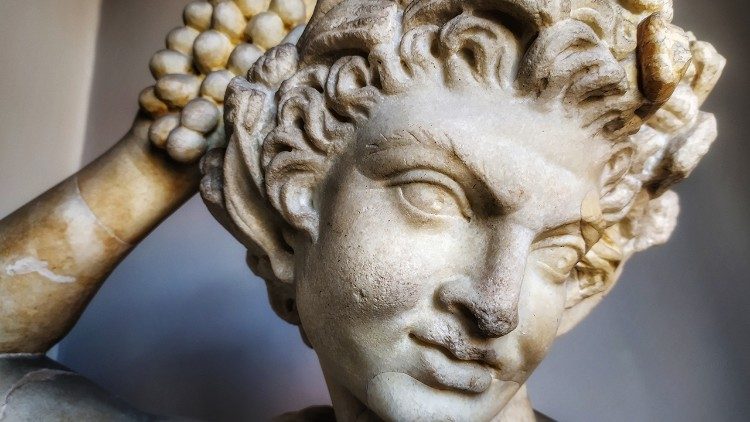

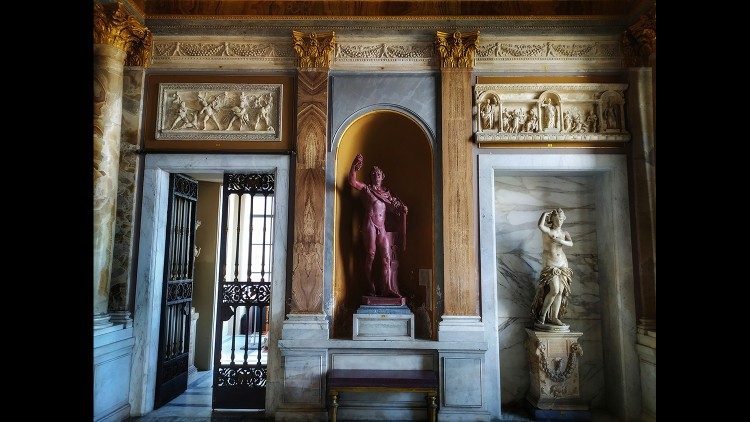

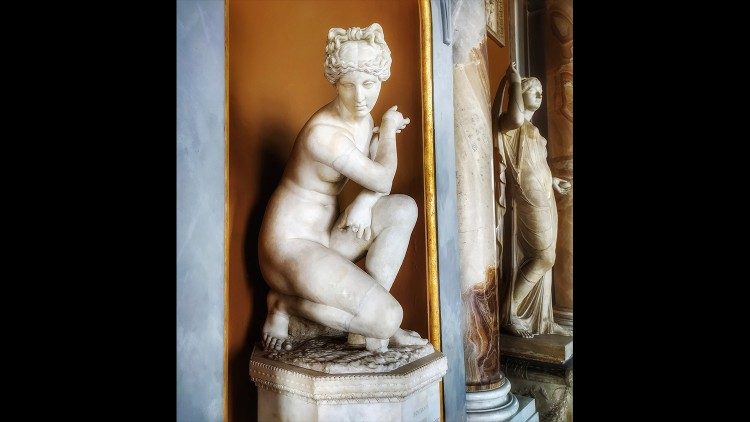

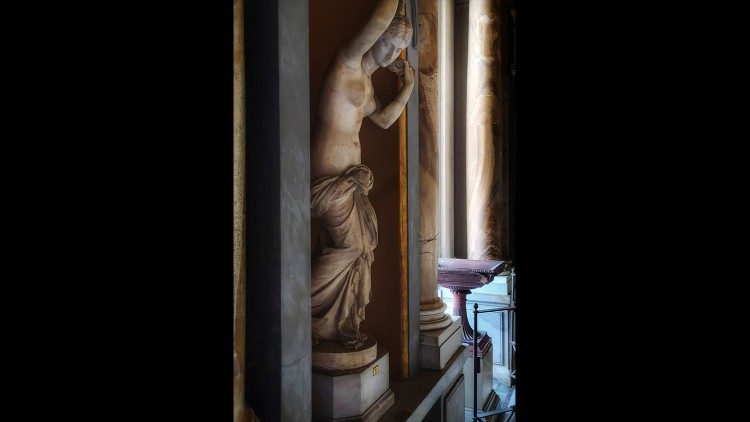

The statue captures the story of the tragic death of the Trojan priest narrated in Virgil’s Aeneid, whose appeal went unheeded not to trust the wooden horse. It was sculptured in Rhodes between 40 and 20 B.C., and is, in fact, a preamble to the foundation of Rome. With Bramante’s help, the Pope, whose name itself is an explicit allusion to an ideological affiliation with the gens Julia, exhibited the Laocoön Group – both he and his two sons enveloped by the coils of two sea serpents – amidst the orange grove and box hedges on Vatican Hill in the Belvedere. He then systematically arranged a collection of other valuable sculptures around the masterpiece: hence the name Courtyard of Statues. Leo X and Clement VI, the Medici Pontiffs who succeeded him, would do the same thing, as well as the Farnese Paul III. Thus a place with diplomatic significance was transformed into an indispensable stage from which renaissance artists could study.

The first museum in the world

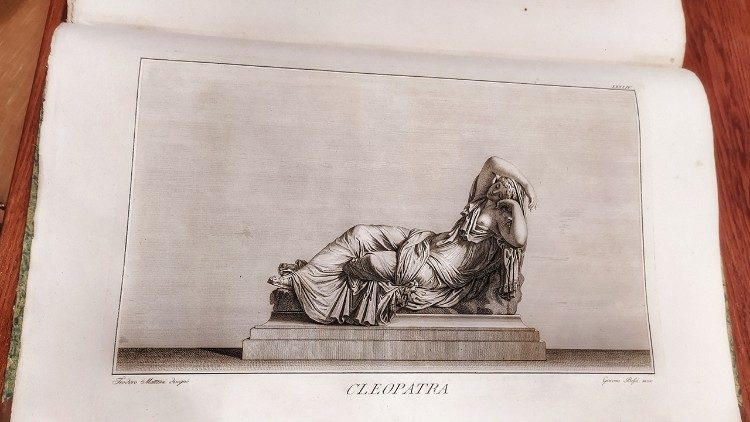

Interest in the profane arts suffered a setback during the Counter-Reformation. Then in the 18th century, Pope Clement XI Albani restored a primary role to ancient statuary in the Vatican – the Pope undertook the conservation of such celebrated statues as the Cleopatra, commissioned the balustrade and the installation of the Bronze Pinecone that had been in the quadriporticus of the Constantinian Basilica, promoted the use of ancient discoveries in the study of Greek and Latin manuscripts in the Vatican Library. It was also in the 18th century that the idea took shape in Rome of opening collections of antiquities to the public. Pope Clement XII Corsini is responsible for the opening of the world’s first museum, the Capitoline Museum, in 1734.

Winckelmann and the treasure of the Eternal City

The Papal State was the place in which museology originated and it soon became the international model. It was the first, in fact, to adopt legislation safeguarding its artistic patrimony. It was an epoch characterized by a true archeological frenzy, nurtured as well by the discovery of the Roman city buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D. From 1709 on, the ancient ruins of the theater of Herculaneum could be traced once again in the Kingdom of Naples. This site was directly controlled by the crown beginning in 1738, while excavations began in Pompeii in 1748.

Johann Joachim Winckelmann was enchanted by the Eternal City where he would stay for thirteen years under the tutelage of Cardinal Alessandro Albani, becoming a point of reference and Grand Tour guide. In 1763 he was appointed Prefect of Roman Antiquities by Clement XIII, whom he remembered as “the Pope who loved me”. This German scholar’s presence in the Vatican, the father of archeology and modern history of art, would leave a lasting impression: “the treasure of antiquities” would no longer be conceived of exclusively in terms of aesthetic value, but as documents to be fully understood so as to reconstruct history. As he would later write on the subject: “I realized that speaking about antiquities basing oneself on books, without ever having seen them in person, is going about it a bit blind”. His bitterness for the many times Rome was sacked over the centuries sharpened his sensitivity to safeguard this artistic patrimony. This is the characteristic he would transmit to Giovanni Battista Visconti, a writer and antiquarian, who would succeed him in his role as Prefect in 1768.

A museum in the Vatican

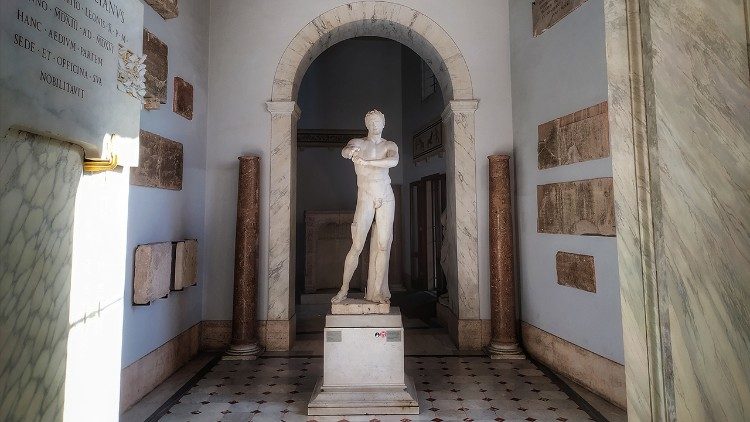

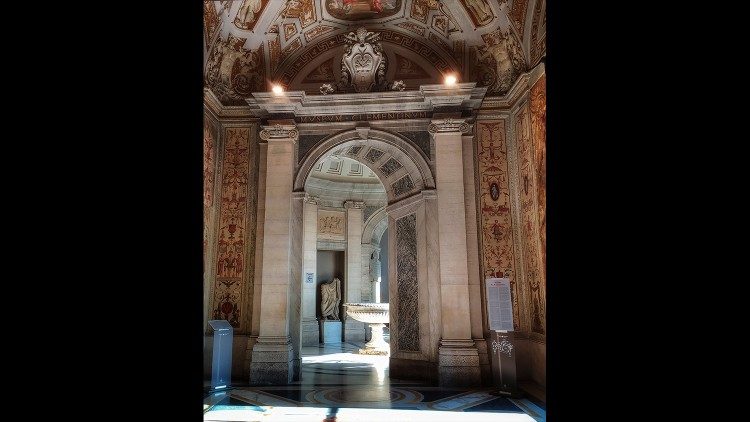

Only a year later, the Franciscan, Clement XIV Ganganelli, ascended the Papal throne. To prevent the dispersal and sale of Roman antiquities abroad, he commissioned the construction of the second public museum in Rome with the help of his treasurer and successor then-Cardinal Giovanni Angelo Braschi. Within six years, the span of his pontificate, thanks to the direction of the Viscontis, new marble statues were added inside the Belvedere Courtyard, constructed by Innocent VIII at the end of the 15th century.

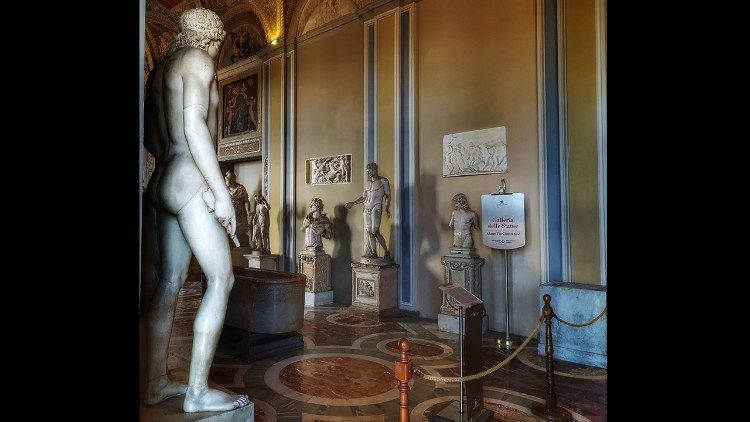

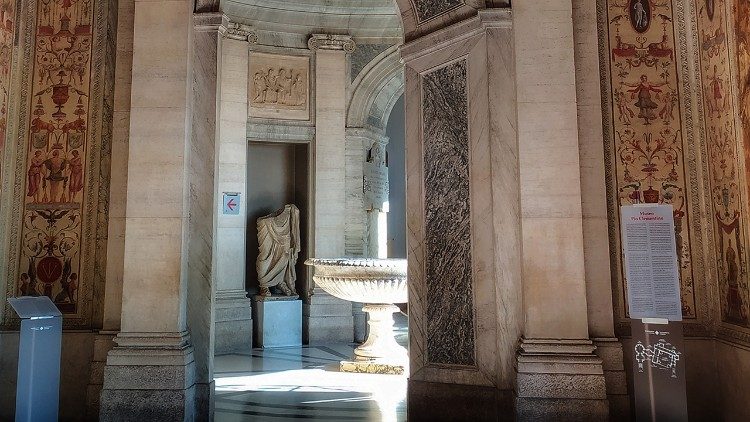

People accessed the new Clementine Museum through the Apostolic Palace via Bramante’s east corridor: the optical deformations of the arch, intended to disguise the diverse orientations of Renaissance and 18th century architecture, the picturesque effect of the Gallery of Statues, its loggia decorated by Pinturicchio and open toward the Roman panorama of Monte Mario, as well as the octagonal design of the Courtyard of Statutes, created a huge impact.

A museum open to the world

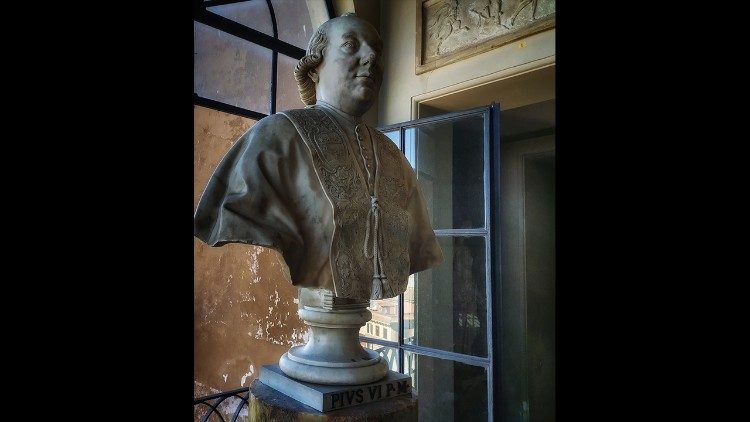

Elected in 1775, Pope Pius VI Braschi remained in continuity with Pope Clement XIV while also being profoundly innovative. He promoted archeological excavations, acquired sculptures, elevated the Vatican Museum project to monumental proportions and provided it with new impetus. In fact, for the first time, a notably large building to be dedicated to the exhibition of antiquities was designed by architect Michelangelo Simonetti.

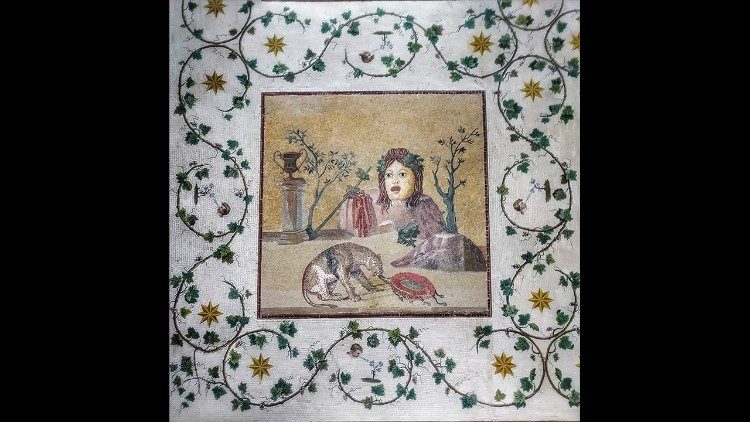

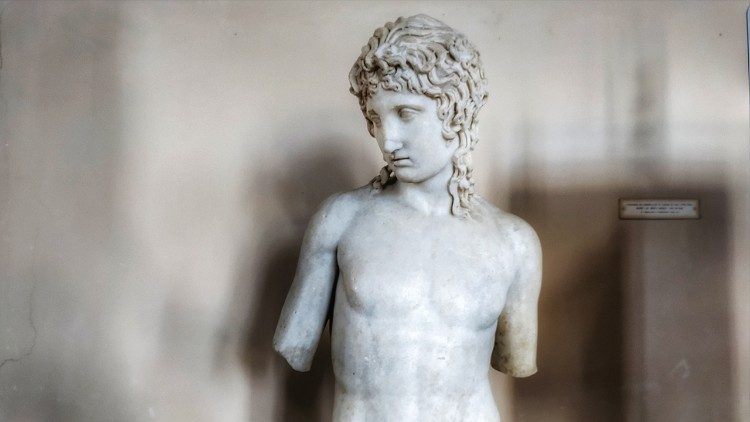

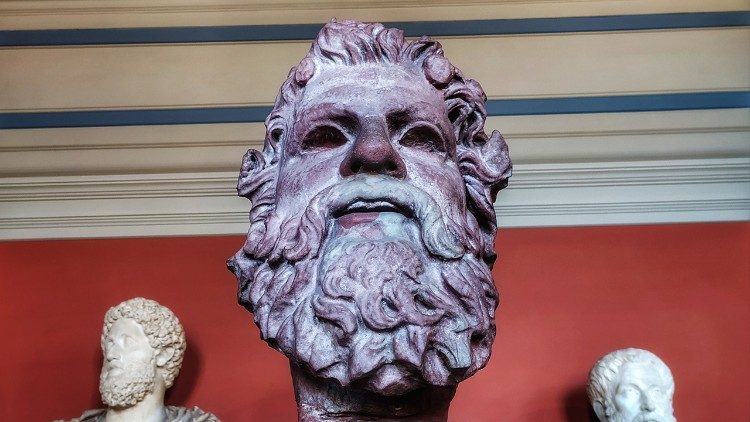

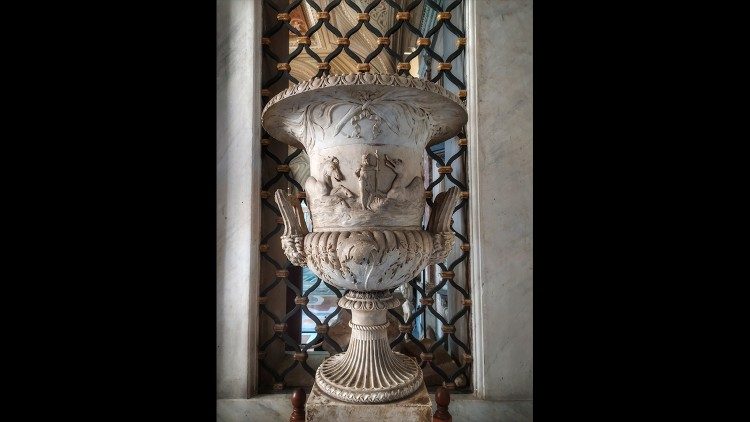

The rooms destined to hold not only statues and busts, but also bas-relief and mosaics, were renovated as archeological discoveries were made. This is the case of: the Sala Rotonda (Round Hall), inspired by the Pantheon, where everything is conditioned by the architectural plan, including the large mosaic flooring discovered in Otricoli; the Sala a Croce Greca (Greek Cross Hall) with the monumental porphyry marble sarcophagi of Helena and Costanza; of the Sala delle Muse (Hall of the Muses) intended to display a series of sculptures discovered near Tivoli with a cycle of frescoes by Tommaso Conca, inspired by Parnaso as a celebration of art and philosophy; and the Hall of Animals, a fascinating marble zoo, designed to house the widest variety of creatures from the animal world according to the encyclopedic spirit of that time. By that time, the Museum, which was then renamed the Pio Clementino, was opened to the outside world. It was no longer accessed through the Apostolic Palace, but through the Vatican Gardens, with an elegant staircase connecting the new buildings to the prior Belvedere “corridor”.

A museum without equal

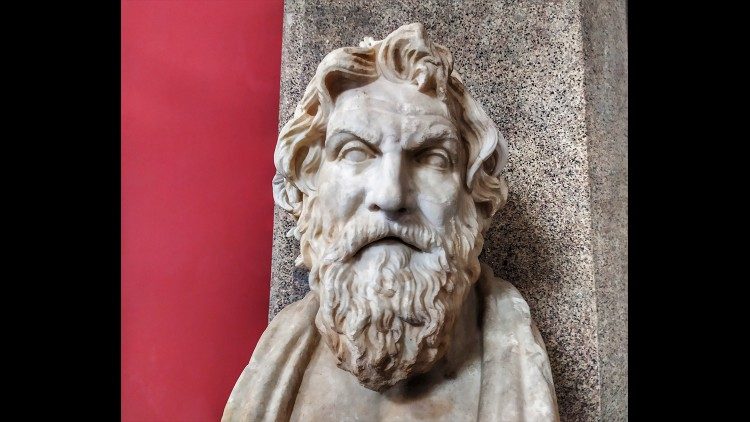

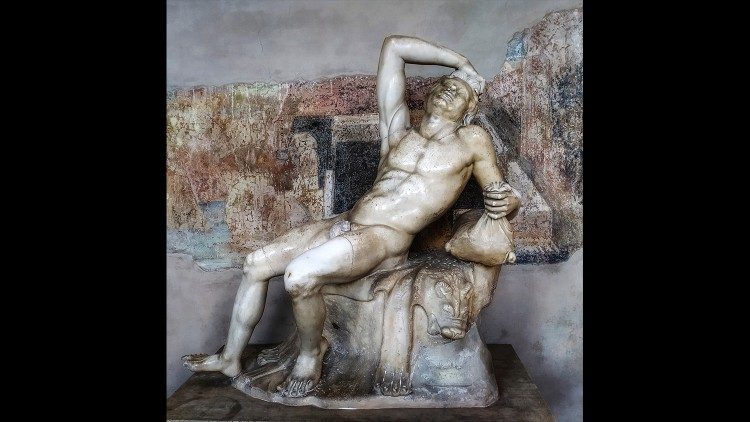

To Giovanni Battista Visconti, and above all to his son, Ennio Quirino, we owe: the correct identification of many statues and reliefs; the promotion of a renewed appreciation of restoration; the recognition of fragments of sculptures as works of art, according to an aesthetic that would characterize the 19th century which caused a bit of controversy with his beloved Maestro, Winckelmann; the important identification of the Sleeping Ariadne, acquired by Pope Julius II, that had until then been identified as as Cleopatra. “This magnificent museum,” Mariano Vasi wrote in his Instructive Itinerary from Rome to Naples, “obscures every other collection of ancient monuments, both in terms of the site’s extension as well as the grandeur of the building, and the immense quantity of marble statues that it contains”.

The works of art in the Pio Clementino Museum – more than 1600 of them – have no equal. And to this day, many people still remain in awe on seeing the Apollo Belvedere, as did Winckelmann three hundred years ago who said, “until now, it is the greatest example of art among the ancient works of art that have been preserved”.

Thank you for reading our article. You can keep up-to-date by subscribing to our daily newsletter. Just click here