Beauty — centimetres within reach

By Paolo Ondarza – Vatican City

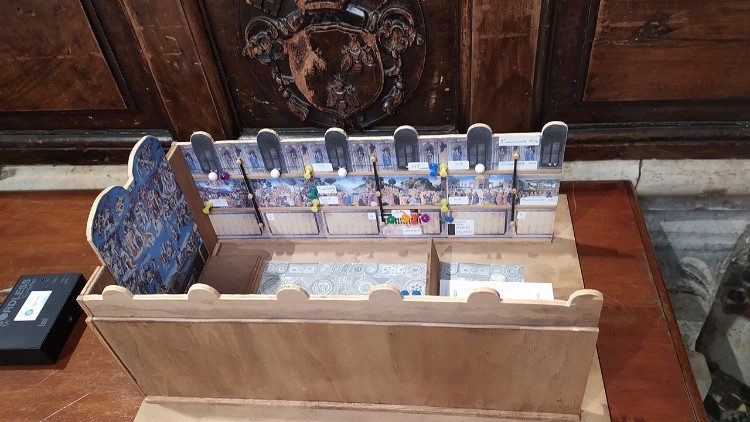

In times past, a person called a mundator was responsible for taking care of the paintings in the Sistine Chapel and in the adjacent Pauline Chapel and Sala Regia. In 1543, Pope Paul III (Alessandro Farnese), instituted the position in a motu proprio, thus revealing the pains the Church, and in particular the Vatican Museums, has always taken to preserve, share and inform people about the invaluable cultural and historical heritage of beauty and faith that the Popes collected and safeguarded over the centuries.

The mundator

After completing the Universal Judgement, Michelangelo had laid down his paintbrushes for only one year when Pope Paul III decided to ensure that this unrepeatable page of painted theology would be dusted periodically, maintaining its splendor unchanged. The task to remove the dust and smoke that had accumulated on the walls was entrusted to Francesco Amadori, known as Urbino, Buonarroti’s assistant in the Sistine Chapel. During the centuries that followed, the painted surfaces of the Sacellum Sixtinum were regularly cleaned with dampened bread crumbs or sponges soaked in Greek wine.

Maintaining a masterpiece

The practice of constant maintenance ceased in the first part of the 20th century. In 1923 when the Painting Restoration Laboratory was established by Biagio Biagetti, who was the Director of the Papal Paintings Gallery at the time, a new era was ushered in, in which constant attention was again paid toward conservation and prevention, and every painting in the Vatican collections was dusted on a routine basis.

The direct heir of the mundator today is the Conservator’s Office. It was established in 2008, thanks to the intuition of the Director of the Vatican Museums at the time, Antonio Paolucci. This office has the task of systematically monitoring the air circulation and temperature in spaces where works of art are exhibited and carrying out ordinary maintenance on all exhibit or warehoused works of art.

In the silence of the night

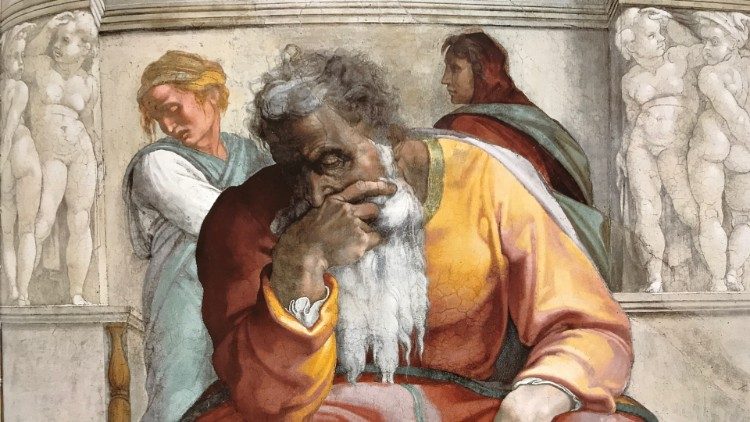

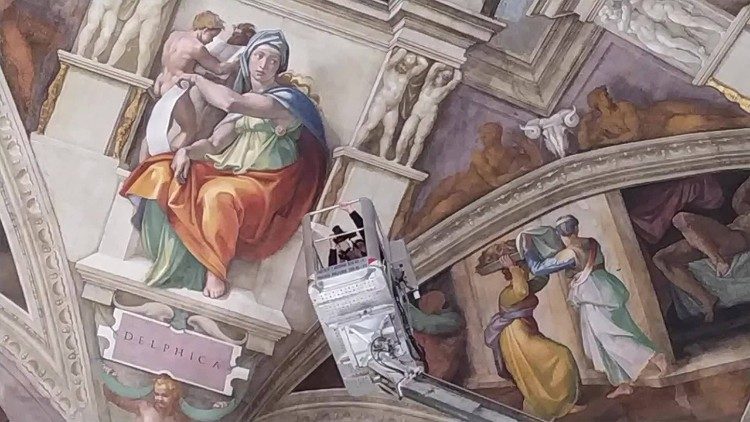

Since 2010, each year between the middle of January and the middle of February, Vatican Museums’ management carries out a program by which all the paintings, lighting, etc. in the Sistine Chapel are inspected, in agreement with the heads of the Governorate of Vatican City State, the Prefect of the Pontifical Household and the Master of Ceremonies. Teams of technicians and scientists alternate every evening between 6:00 and 11:00, as soon as all the tourists have left, keeping to a tight schedule. They make use of two ‘spider’ scaffolds, mobile platforms equipped with mechanical arms, to reach a height of 20 meters where they find themselves one-on-one with Michelangelo’s brushstrokes.

In direct contact with history

The emotion is indescribable, even for those in the profession. “Although we do it every year, the power of the experience never dims”, explains Vittoria Cimino, Director of the Vatican Museums’ Conservator’s Office. “It means pulling together instantaneously everything we have ever studied or thought about that is present on a cognitive level inside our heads. To go into the Sistine Chapel when it is empty, silent, puts us into direct contact with history, with the history of art, with the theological significance of these magnificent paintings”.

Emotion and responsibility

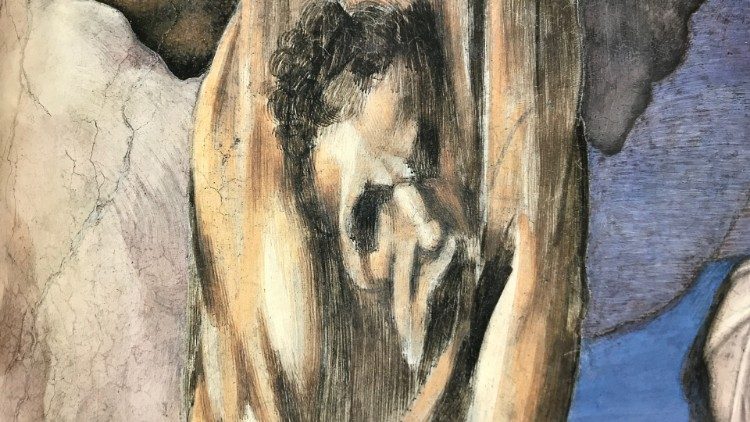

Francesca Persegati, Director of the Vatican Museums’ Painting and Wood Materials Restoration Laboratory, shares this view: “Every year, those of us who work in the Restoration Laboratory tackle a portion of the frescos to inspect a surface area measuring 2,500 square meters within a limited amount of time. It’s a huge responsibility. When I think about it, I get a bit emotional because at times you wonder if you’re worthy, especially when I think about the great people, such as Biagio Biagetti, who have preceded me. Then reason calls us back to the task of establishing a physical relationship with the work, entering into it, touching it. There’s always a moment of apprehension because scientific knowledge is not enough. We are called to conserve this work of art and to pass its message on to future generations. Michelangelo used a good fresco technique because he wanted it to last as long as a sculpture. Today, the state of conservation of these paintings is very good”.

Inspecting one-of-a-kind frescos

The system for monitoring is fundamental. Vatican restorers, as the mundator once did, remove the dust first of all, otherwise dust particles could cause the surface of the wall to deteriorate. Then they monitor the paint pellicle, the plaster, the possibility that the paint is detaching from the wall, or the presence of salts deposits that are removed with sheets of Japanese paper and distilled water applied with a brush.

Thirty hidden sensors

Climbing up the scaffolding not only allows direct contact with the frescoes on the ceiling, but it also makes it possible to verify that all thirty sensors hidden along the cornices that monitor the air are functioning correctly. The philosophy that guides the specialists at work is: “less restorations and more preventive conservation and maintenance plans”. According to Vittoria Cimino, “restoration is never a painless intervention for the stability of a work of art and must always be carried out only when extremely necessary”.

Prevention as conservation

“To conserve means to maintain each piece of art in good condition, without material intervention”, the Director of the Vatican Museums’ Conservator’s Office continues. “It is, therefore, fundamental, that conservation needs to be continual rather than sporadic and include utmost attention regarding the area in which art is conserved or exhibited”.

Over 6 million visitors cross the threshold of the Sistine Chapel each year. Constant observation of changes in air pressure produced by the presence of all these people, or changes to the environment such as humidity and temperature over the passage of time and seasons is essential. For example, “visitors produce carbon dioxide, water vapor, humidity, heat. These are all factors that are harmful to works of art that must live in a constantly stable environment”. The sensors record all the variations in the established parameters within the 10 thousand cubic meters of air in the Cappella Magna, thus allowing for the calculation of the number of people present at various times of the day through an algorithm used in connection with a system of thermal cameras. In this way, the amount of dust in the air as well as air speed, direction and pressure and other variables are measured. This network of sensors is accessible remotely at all times by those who work in the Conservator’s Office.

Best air in the Vatican Museums

The annual results of this monitoring is encouraging, Vittoria Cimino says. “Thanks to a new air conditioning and purification system that was designed and installed by Carrier technicians, by the Infrastructure Department and by the Services of the Governorate”, she adds, the air in the Sistine Chapel “is the best in the entire Vatican Museums”. “Annual inspection confirms a stable situation suitable for conservation. Our experience”, she continues, “leads us to affirm that, within a museum, various cultures need to be in contact with each other – human, historical, artistic, as well as technical and scientific. At the service of both Beauty and Faith is the experience obtained through science which assists the professionals’ trained eyes”.

Humanism and science in dialogue

Results of the interdisciplinary dialogue between the humanistic and scientific disciplines are notable. For example, a new LED lighting system able to match the spectrum of natural light was recently installed in the Sistine Chapel with amazing results. Visitors are now able to see the frescos in an entirely new light that enhances to the maximum the colors Michelangelo used.

Michelangelo’s brilliance rediscovered

The brilliance of those colors, as Biagetti had already intuited in the 1930s, was hidden under a coating of smoke. It completely came to light during the 1990s with the restoration undertaken under the direction of recently deceased Gianluigi Colalucci. “That restoration”, Francesca Persegati recalls, “changed our perception of Michelangelo. He emerged not as a grumpy, dark artist, but as bright painter who did not make use of the chiaroscuro technique for shading, but used color”.

Several areas of the fresco were not restored, thus leaving portions still covered by the film deposited over centuries clearly visible as evidence. Even the history of a masterpiece as it was seen over the various eras it has survived is a value to preserve and pass on.

Thank you for reading our article. You can keep up-to-date by subscribing to our daily newsletter. Just click here