The periphery at the center

Paolo Ondarza – Vatican City

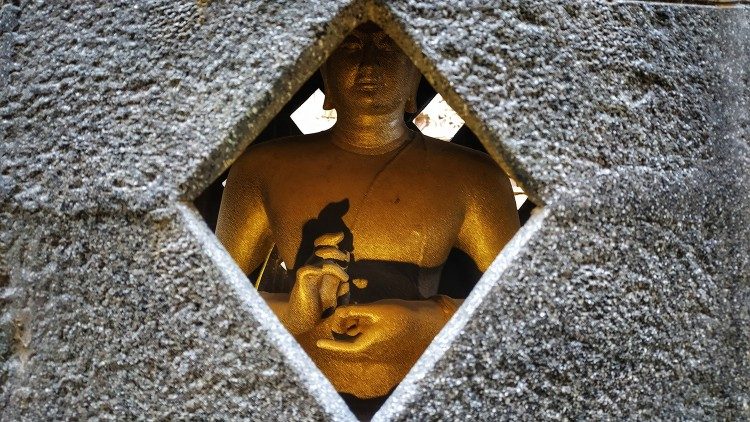

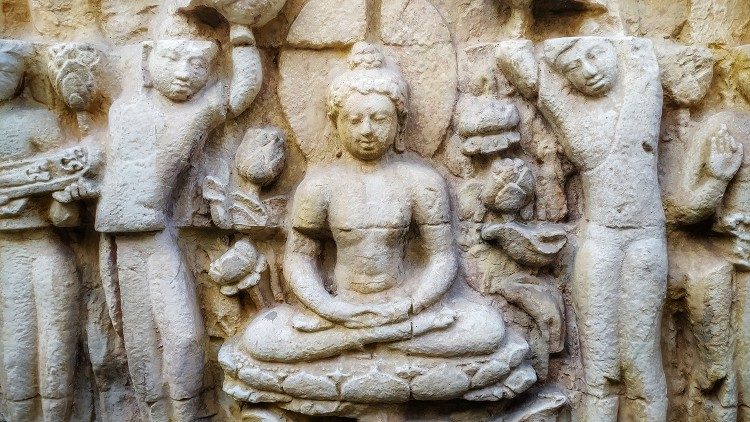

From disorientation to amazement, from curiosity to the desire to get to know distant cultures and traditions. It’s the emotional journey of those who visit the Vatican to admire the masterpieces of Raphael and Michelangelo, who then enter the new premises of the Ethnological Museum, now called Anima Mundi (spirituality of the world). It is not just any other exhibit, but beckons to inclusiveness and dialogue. It’s a space in which to respectfully draw near to non “western” aesthetic canons. Here art becomes pluralistic. It takes on an international, universal, catholic approach. It’s a museum whose center is the periphery.

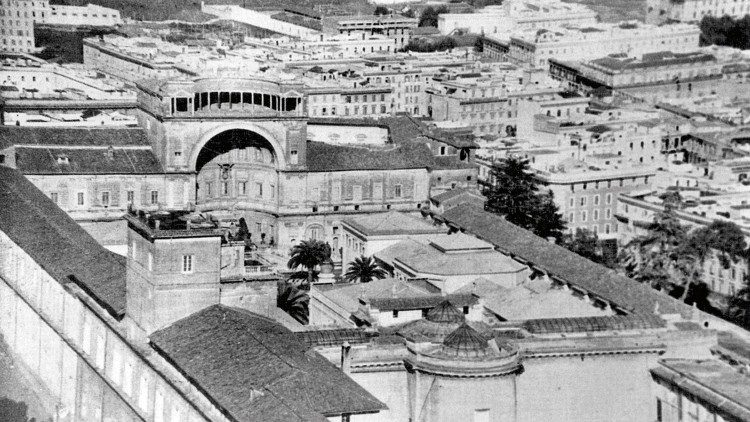

Vatican Mission Exposition 1925

The first nucleus dates back to a donation of pre-Columbian artifacts more than three hundred years ago. But what really launched the collection was the highly visited Universal Missionary Exposition Pope Pius XI founded in the Vatican in 1925. At a moment in which Europe was ravaged by the spirit of nationalism, a million people had the possibility of admiring more than 100 thousand artifacts coming from all around the world, including from those parts of the earth tainted with the prejudice of being “savage”. It was a powerful testament of a Church with open doors.

Forty thousand of these artifacts remained in the Eternal City. Their fate was sealed by the Motu proprio Quoniam tam praeclara, dated 12 November 1926, founding the Missionary Ethnological Museum. It was originally directed by the Divine Word Missionary Father Wilhalem Schmidt, and hosted in the Lateran Palace. Under Pope Paul VI in the 1970s, it was transferred to the Vatican Museums.

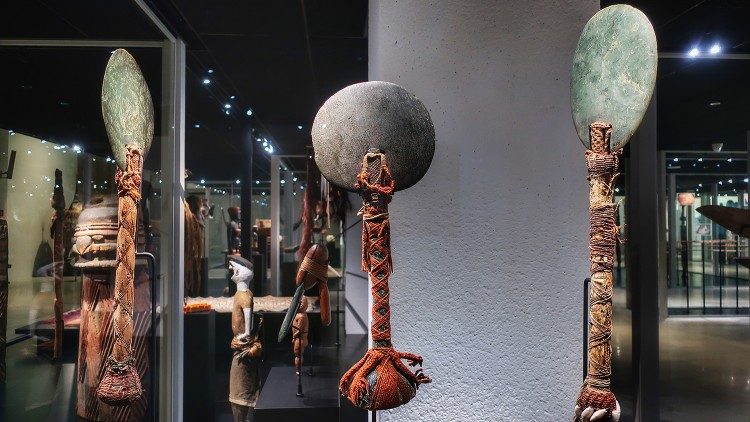

Objects as representatives of peoples

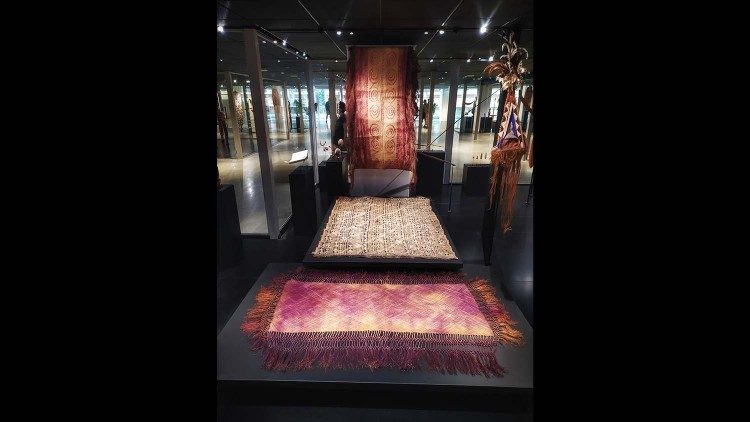

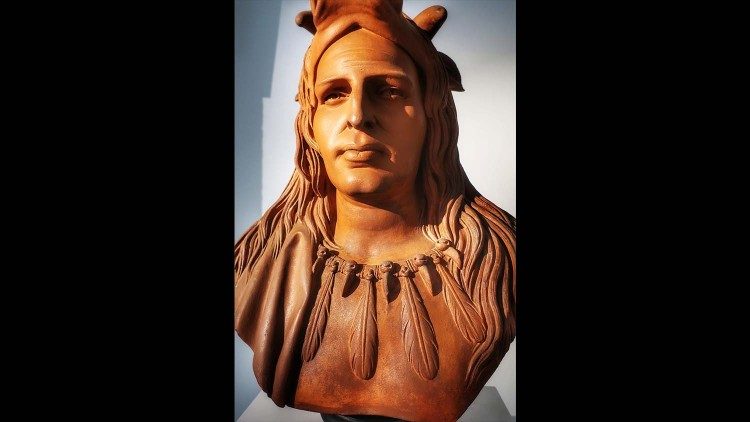

Today, the Anima Mundi Museum contains approximately 80 thousand artifacts and works of art. They come from Africa, the Americas, the Pacific, Australia, Asia, the Islamic world, as well as prehistoric and pre-Columbian civilizations. “The artifacts”, PIME missionary Father Nicola Mapelli, Curator of the Anima Mundi Museum, explains, “are cultural ambassadors. They speak of the peoples from which they come: from Papua New Guinea to Alaska, from Australia to the Sahara Desert, and Asia. Dynamism and vitality characterize the history of the artifacts. This type of art, in fact, has never died and is not static. It continues to nurture itself even today through its relationship with the places and peoples where they originate, with their beliefs and vision of life”. It is an inclusive collection, a manifesto; it is the voice of peoples whose basic rights are often endangered or violated.

Reconnecting

The Museum builds bridges. It sparks dialogue. It is a means to protect the human dignity, the patrimony and legacy of peoples far distant from us in terms of space and time, with whom we share the same humanity. Due to this sentiment, respect for the cultures, and the desire to preserve the semantic and symbolic value each object bears, “reconnections” happen. Father Mapelli has gone to the countries where the artifacts come from and has met with the local peoples. “It is important for us to be in dialogue with these peoples”, he said. “For example, to set up the section dedicated to Australia, the first so far open to the public, we went to the villages where the artifacts we preserve come from. We asked the Aborigines the meaning they attribute to what they create and how they desire they be displayed to our visitors. When possible, this is what we try to do for each individual object”.

Gifts given to the Pope

Most of the artifacts in the Anima Mundi Museum are gifts the Popes received in past centuries or gifts that were sent to the Vatican from far off lands. Some of them were “repatriated”, as, for example, is the case of a tsansa, a human head, reduced in size, used for ritual purposes by an Amazonian Jivaro tribe, recently “repatriated” by the Vatican Museums to Ecuador.

Stories

Behind each object is a story. A moving meeting took place between Father Mapelli in aboriginal territory straddling Australia and Indonesia, with a descendant of the creator of one of the poles carved and painted on the Tiwi Islands. “At the age of eighty, this woman remembered her grandfather who, when she was a child, would take her on his knee while he was carving these poles, telling her that what he was making was for a person who lived really far away and was important: it was the Pope! That woman embraced me because in some way I was bringing the story and her grandfather home to her”.

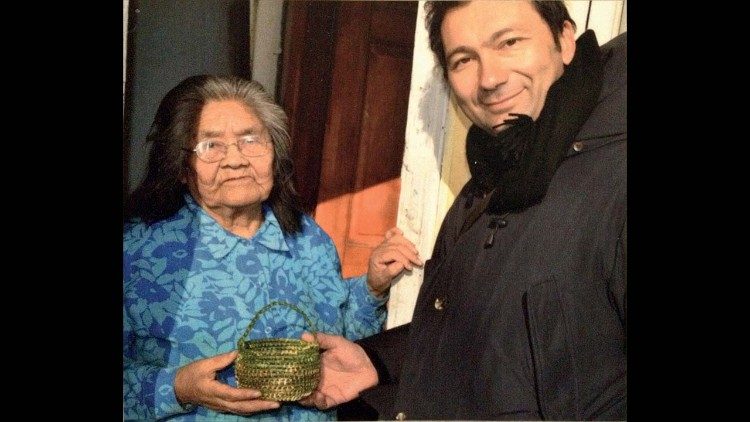

A mask and basket

From the archipelago of the Tierra del Fuego in Patagonia comes a memory preserved in a ritual mask from the Island of Navarino sent to Rome during the 1920s by missionary Father Martin Gusinde. “We succeeded in finding the descendent of Father Gusinde’s interpreter. As a token of her gratitude, the elderly woman made a basket for me while I was visiting her. We put it on exhibit here in the Vatican Museums alongside the ritual mask of Navarino”.

The shipping of a statue preserved in the Vatican for an exhibit in Polynesia was also moving and filled with meaning. When it departed once again for Rome, a thick fog settled over the island: “The locals attributed it to a melancholic good-bye that their land paid to the artifact”.

Without confines

Anima Mundi is a place without barriers. When Pope Francis inaugurated the exhibit halls on 18 October 2019, he said, “Those who enter here should feel that in this house there is room for them too, for their people, their tradition, their culture. All peoples are here, in the shadow of the dome of Saint Peter’s, close to the heart of the Church and of the Pope”.

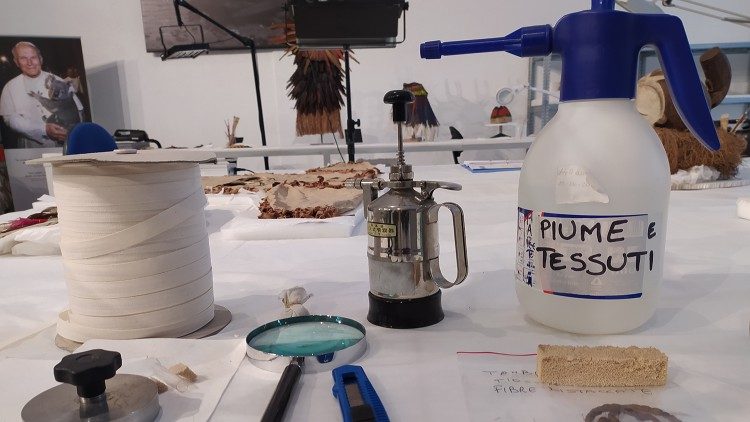

See-through laboratory

As transparent as the glass in which the artifacts are displayed are the walls that enclose the temporary premises of the Ethnological Materials Restoration Laboratory. Once work is complete on what will be its permanent place, visitors will be allowed to observe restorers at work. In this way, the experience of how these artifacts are conserved can be shared.

Conservation, research, dialogue

“Over the course of my twenty years in the museum”, says laboratory director, Stefania Pandozy, “we have changed the approach we use for restoration from a western, Eurocentric, to a post-colonial vision. We understood the necessity for ethics and responsibility in conservation. We had the conception of this Museum as a treasure chest containing thousands of objects of tremendous value, but we did not imagine that we were dealing with living people, living civilizations, treasures prevalently organic in origin, that tell something about the communities from which they originated at the time they were made. Anima Mundi is truly a museum of contemporaneity. This experience allows us to be in contact with a variety of indigenous materials from all types of non-European cultures. Together with the Department itself, we seek to involve the community of origin in making choices regarding conservation and exposition. At the basis of our work is a constant commitment of appreciating diversity. Our goal is that of sharing the conservation experience to promote the educational function of the laboratory as a place of research and dialogue”.

Restoration ethics

The staff in this unique Laboratory is composed solely of women, each with her own specialty in different types of materials. Comparing and sharing information on an international level gave birth to The Ethics and Practice of Conservation, edited by the Laboratory, the first manual in the world regarding the conservation of ethnographic and polymateric artifacts.

“An ethic of conservation”, Stefania Pandozy continues, “is possible and can be synthesized in a careful analysis of both the context of origin and the current “moorings” of the ethnographic object in dialogue with today’s indigenous communities. This is a paradigm shift that proposes professional and human challenges to all those working in the cultural sphere, aware that our contemporary society, which pays too little attention to collective well-being, can and must become more solidary, more inclusive”.

International exchange

“Our dream is that of opening an international school in the Vatican to educate young generations of restorers in conservation so as to pass on both the knowledge and techniques that would otherwise run the risk of being lost”.

The commitment to this new approach to conservation is shared by many restoration laboratories throughout the world. “We have had the opportunity of experiencing this reality even by going to places of origin. This is the case of the Christopher Columbus’ Missal case, which remained on display at the Palace of Captains-General in Havana, Cuba, in 2012. It was a huge opportunity to exchange experiences and professionalism with the Restoration Laboratories of the Gabinete de Conservaciòn y Restauraciòn de La Habana”.

Sharing Conservation

One example of ‘Sharing Conservation’ is the work carried out by the Laboratory together with an expert ornithologist called on occasionally for the restoration of an extraordinary Mekeo headdress, from Papua New Guinea. It is the oldest in the world. Identifying the bird species and studying the feathers used made it possible to collect a standard sample representative of all the plume and feather colors found in nature, and represented in the Museum’s collections. This precious collection was used to launch, in collaboration with the Vatican Museums’ Scientific Laboratory, a cutting-edge experiment on the use of laser technology for cleaning feathers.

Sustainability

From the perspective of sustainability, in conjunction with the Cabinet of Scientific Research applied to Cultural Heritage and the other Restoration Laboratories of the Vatican Museums, a “Polymateric” team has been active for years conducting research on natural materials and biocompatible products, which in some cases have been found to be more durable than synthetic ones.

Visible deposits

The Anima Mundi collection is also a symbol of openness and hospitality. It consists of one large see through box, air-conditioned and constantly monitored. Above the exhibit space, 98% of the Museums’ entire bird collection is displayed. The Museums’ overall project, which now consists only of an area dedicated to Australia and the Pacific, envisages the construction of other continental sections as well. They will be interconnected among themselves, without boundaries, such as walls or other barriers; illuminated by natural light coming through large windows, appropriately filtered for conservation purposes. This creates the atmosphere of sunlight cutting through the dense, luxurious vegetation of the Amazon forests, or lighting up the Sioux prairies, or radiating off of and warming the desert sand.

Beauty that unites

“To understand that a Sioux dress is not just a garment, but that it signifies the life of a people, the hands of the women who sewed it, the purification ritual, the beating of drums, the sun dance”, Father Nicola Mapelli explains, “means going beyond your own knowledge, to put yourself into motion”.

To the present, this attitude continues to inspire the missionary vocation of the Anima Mundi Museum as its artifacts find their way into memorable international exhibitions: Cuba in 2012; the United Arab Emirates in 2014, the first of its kind to take place between the Vatican Museums and an Islamic country; in Canbarra, Australia in 2018, where for the first time, the Vatican Museums collaborated with two other Museums – the Sharjah Museum of Islamic Civilization and the National Museum of Australia – to create a joint exhibit of Islamic art, a testimony to the dialogue and mutual understanding between cultures and religions; in China, in Beijing, the Forbidden City, in 2019. It represents a commitment in the name of beauty, different types beauty, beauty that unites.

Thank you for reading our article. You can keep up-to-date by subscribing to our daily newsletter. Just click here