Michelangelo’s “Teacher” - first episode of the series "Celata Pulchritudo"

by Paolo Ondarza – Vatican City

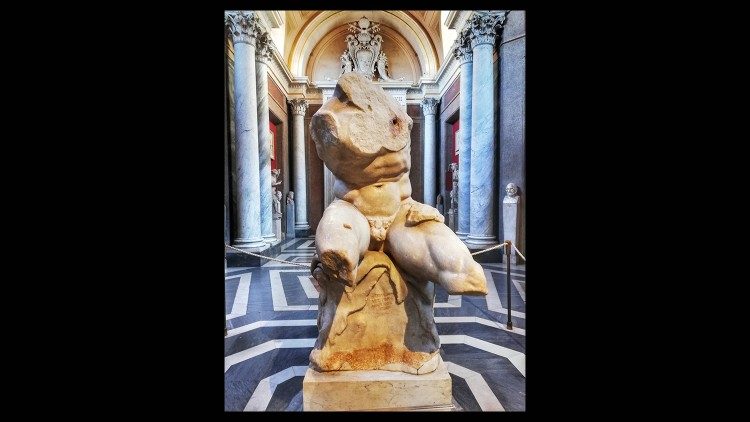

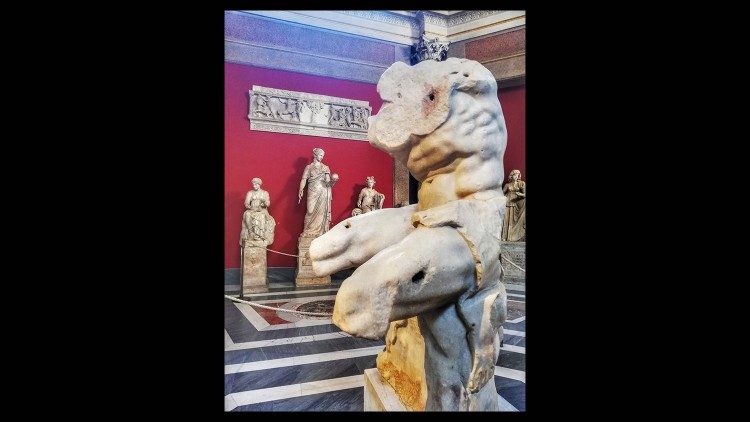

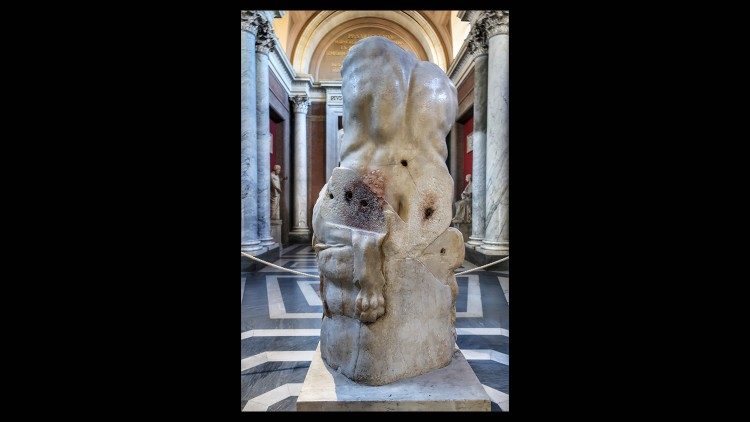

Mystery and beauty, unaltered by the passage of time and history, radiate from the Belvedere Torso, an identifying work in the Vatican Museums housed inside the Pio Clementino Museum.

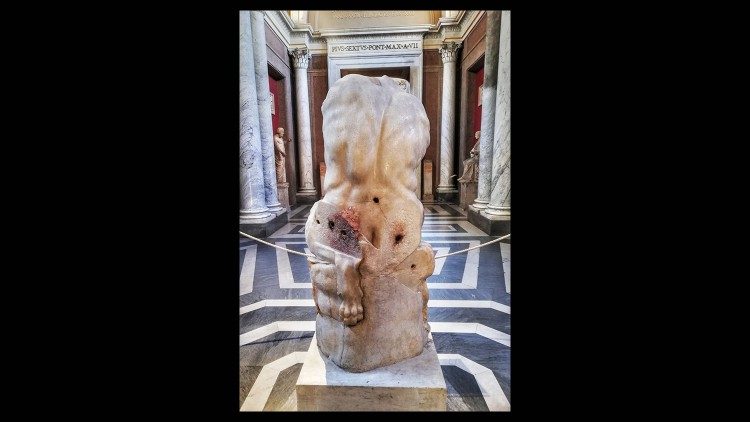

The Greek fragment bears the signature of a Neo-Attic sculptor, the Athenian “Apollonios, son of Nestor”, from the first century before Christ. It is probably a marble copy, inspired by a bronze original, sculpted between 188 and 167 B.C. Identifying the subject is enigmatic due to its incompleteness: Dionysius, Hercules, Philoctetes, Polyphemus? The interpretations have been multiple and at odds. Only recently, thanks to a lengthy archaeological study and the reconstruction of the pose through the observation of live movement, a highly credible hypothesis has been proposed that identifies the subject as the Greek hero Ajax Telamonius in the act of contemplating suicide.

Static tension

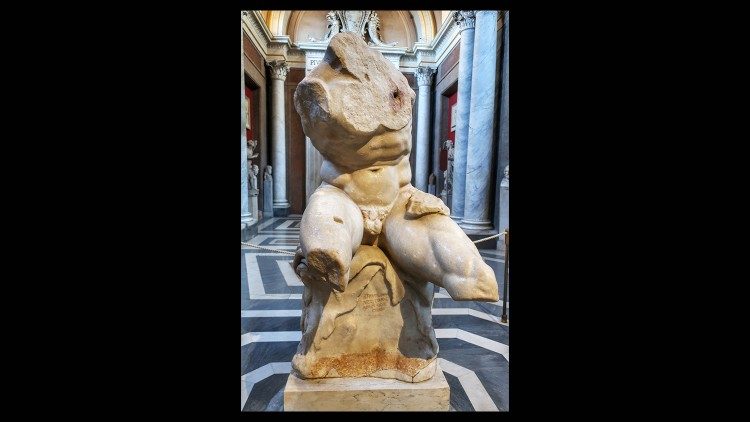

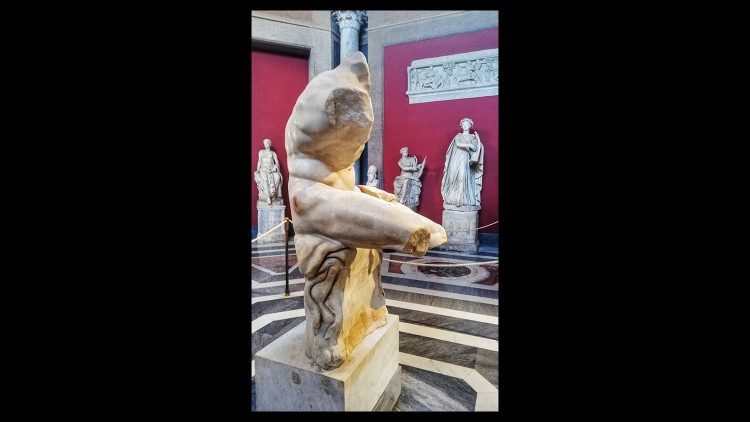

The anatomy presents a body in tension. A “static tension” (static position with muscle tension), was used in classical art to depict characters who were contemplating death. This is how Giandomenico Spinola, Curator of the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities and head of the Archaeology Department of the Vatican Museums, defines it: “The static position associated with muscular tension at the highest levels depicts a psychological tension, suggests contemplation, deep and penetrating thought. What he is contemplating makes him tense. Static tension has in fact always been used to depict people who are looking on death or contemplating death”. The moment being immortalized is the one in which Ajax contemplates suicide after being defeated by Ulysses in the struggle for Achilles’ weapons. He is furious, has lost the ability to reason and has killed a flock of sheep, mistaking them for enemies. He then sits down on an animal skin, perhaps that of a panther, and contemplates suicide. His head rests sadly on his right hand, which was probably grasping the sword with which the hero killed himself. In his left hand, instead, he grasps the sheath. The holes in the marble present the missing parts to the imagination: his limbs, his shield, his sword, and probably other human and animal figures that made up the complex sculpture.

A masterpiece amidst the flux of the Museums

As the approximately twenty thousand tourists file through the Vatican art collections’ halls every day, taken in by the multiple aesthetic stimuli that bombard their eyes, the greatness of this masterpiece risks not being grasped to its full extent. Located today in the Hall of the Muses, along the way that leads to the Sistine Chapel, the tourist first sees the Torso from behind, it immediately imposes itself in terms of strength and physical beauty. “Many tourists”, Giandomenico Spinola comments, “come here and do not realize the Torso’s importance. Only a few appreciate it. The visitors run to get to the Sistine chapel. The rush of the crowd leads them right by it”.

The Octagonal Court

Included by the engraver William Hogarth in his canons of beauty, the Torso, has been a school for entire generations of artists: from Michelangelo to Rubens, to Turner, to Rodin who drew inspiration from it for the famous “Thinker”. The place and time of its discovery are unknown. According to the journals of the archaeologist and epigraphist Cyriacus of Ancona, as of 1433 it was housed in the Colonna Palace on the Quirinale Hill. The Torso unleashed its ability to fascinate from the moment it was taken to enrich the collection of Cardinal Giuliano della Rovere. Around 1503 after his election to the papal throne, under the name Julius II, he decided to move it to the Vatican’s Octagonal Court (formerly known in Italian as the Courtyard of Statues). Since the early sixteenth century, some of the most beautiful works of all antiquity have been housed here. These include the Pythian Apollo, known as Apollo Belvedere, and the Laocoön Group, which in 1506 was prodigiously extracted almost intact from the earth.

The birth of the Vatican Museums

It was Julius II who authorized the birth of the future Vatican Museums. The Belvedere Court, or Courtyard, would become a studio that would initiate young artists who came from all over. Guido Cornini, scientific director of the Arts Department of the Vatican Museums, calls it the “school of the world”, citing the expression used by Benvenuto Cellini in connection with the “battle” paintings created by Leonardo and Michelangelo for Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio.

School of the world

“It is the period”, Cornini says, “in which the Laocoön Group was found. In 1506 it was extracted miraculously from the earth, almost intact. It had survived the Middle Ages. There was enormous enthusiasm. The cultural climate was dominated by a passion for archaeology and the antiquities. Artists from all over the world, especially Flemish artists like Hendrick Golttzius, began to flock here to copy, take notes, draw sketches, make the first prints, to become familiar with the great Belvedere marble statues”. It was the Renaissance, the moment when the connection with the great Greek and Roman civilizations of the past, abruptly interrupted by the barbarian invasions, was redeemed and reinterpreted in a Christian light.

Michelangelo and the Torso

Michelangelo, the leading artist on Julius II’s team, was captivated by the charm of the Torso, one of the original Greek survivors of the “shipwreck of history”. He immediately felt his “sculptural technique” was in complete harmony with Apollonios’s. It is said that he rejected the Pope's proposal to add the mutilated parts of such a perfect, powerful work, so robust in its accidental incompleteness. The Tuscan maestro’s journals recount hours and hours spent in ecstatic admiration in the company of the Greek masterpiece. By touching the marble he established a physical and spiritual relationship with it. He was almost hypnotized by the static tension of Ajax contemplating suicide.

Disciple of the Torso

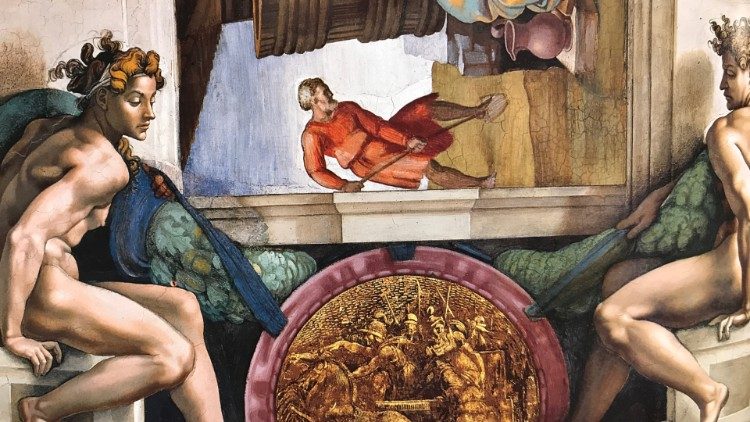

Michelangelo was rightly described as the “disciple of the Torso”. The Ignudi on the Sistine Chapel ceiling bear witness to this in their marked plasticity: “Athletic, muscular, these figures, almost aptera angels,” continues Guido Cornini, “are straining, but their gesture appears unfinished”. It is no coincidence that the famous scholar, Charles de Tolnay, speaks of the evident “dissipated energy” in the swollenness of the limbs and the inflation of the muscles. Some have recognized in the agitation of the Ignudi, the restlessness of the pagans who have not known Revelation. They are blind. Their backs are turned away from the biblical scenes frescoed on the ceiling. “Their postures in a certain sense memorialize the Torso, which Michelangelo saw, studied, and examined at length”. The two nudes with garlands flanking the scene of “Noah’s Sacrifice” seem to be almost accurate reproductions. “The strong sense of agitation coming from the ceiling is strong,” Cornini adds. “It also penetrates the figures contained in the Last Judgement, or the Moses in the Church of St. Peter in Chains in Rome”. Also evocative is the combination of the incompleteness of the Torso and of Michelangelo’s other non-finito works, such as his Prisoners or Slaves, all characterized by “a sense of uneasiness, of an undefined effort being made: it is as if they are struggling, struggling to free themselves from the material that imprisons them”.

Thank you for reading our article. You can keep up-to-date by subscribing to our daily newsletter. Just click here